Ana Mendieta’s Conceptual Performative Practice

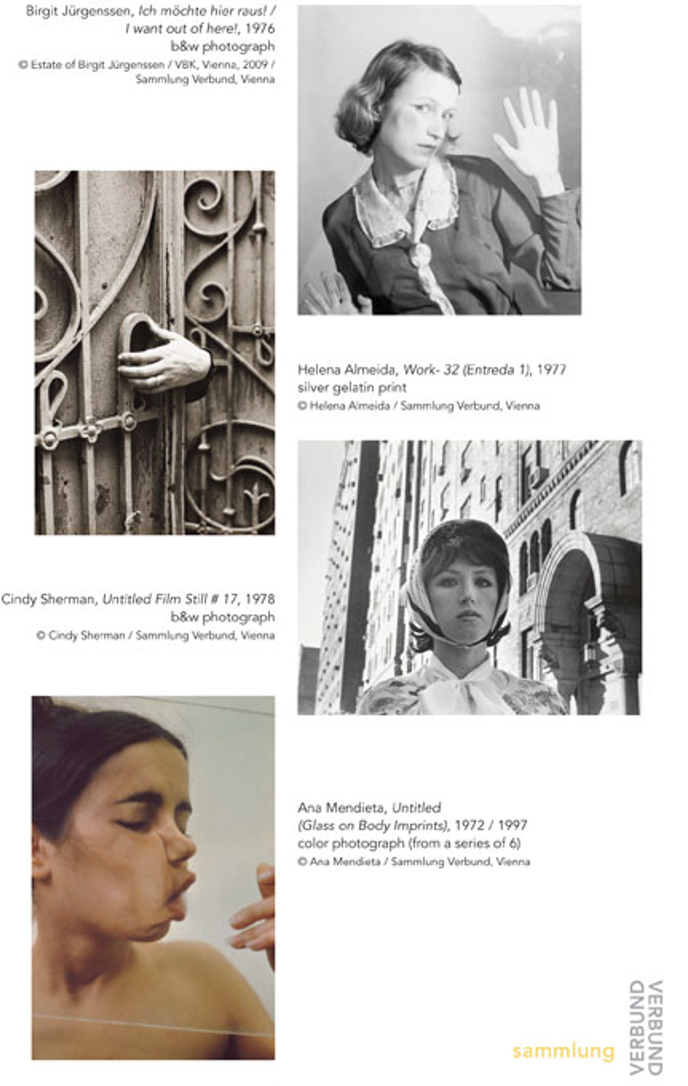

Americas Society, New York, June 2005 | Miami Art Museum, Miami,Oct. 2005

Lecture by Julia P. Herzberg. All images are reproduced for non-commercial scholarly and educational purposes only, in accordance with fair use. Copyright remains with the respective artists, estates, and rights holders.

Ana Mendieta [1948-1985] is renowned for pioneering a genre of art that combined performative actions, body art, photography, and sculpture. Born in 1948 in Cuba, she emigrated with her sister to the United States in 1961 as part of the Pedro Pan exodus; the Mendieta sisters were resettled in Iowa where they were raised by different foster families until their mother joined them in 1968 and their father in 1979.

From 1970 to 1972, Mendieta was a graduate student at the University of Iowa majoring in painting and drawing.

Ana Mendieta, Autoretrato, 1969, oil on linen

From 1972 through 1977, she was enrolled in the Intermedia Program where she began by doing performative body art, which quickly evolved into earth-body sculpture. Working in Iowa during the academic year and in Mexico during the summers, Mendieta used her body or its outline, the silueta, to create what is today considered her hallmark work.

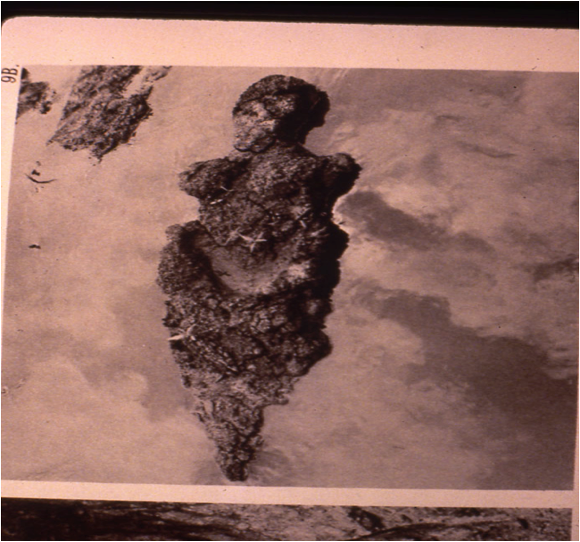

Ana Mendieta, Sin título (Precolombian Figure), s/d 1970

In 1978 Mendieta moved to New York where she began to broaden her art world connections. On her frequent return trips to Iowa, she worked in nature, reconfiguring the body outline with a variety of natural elements.

Ana Mendieta, Silueta (3 contornos quemados en el suelo) Agosto 1977

As her work evolved in the ‘80s, the silueta referred to an archetypal female image that is both self-referential and of mythical origins. The artist’s diverse aesthetic modes simulated a sense of magic, ritual, and power that she found in the art and celebrations of non-western peoples.

Ana Mendieta, Sin título (silueta sobre un arbol caído con musgo), Iowa, 1978

I will focus on Mendieta’s formative period, her evolution in Iowa and Mexico from ’70 through ’77, during which time the artist’s work set the parameters for her subsequent development.

Ana Mendieta, Body Tracks, 1974

[Then I will indicate the shifts that occurred as her work continued to mature from 1978 until her death in 1985]

Ana Mendieta, Sin título, Roma, 1985 (dos de cuatro esculturas de arboles de madera y pólvera)

Mendieta’s formative period, from 1970 through 1977, has multiple strands: she stopped painting and began conceptual body work in the Intermedia Program; she taught art to elementary students at experimental schools (Kirkwood and Sabin) in Iowa City (from 1973 to 1975) where she integrated ideas from her own practice; and she concentrated on site-specific work in Mexico and Iowa.These strands were connected conceptually, and thus reinforced the work she did from place to place.

Totems, enero a marzo 1975. Projecto de arte por Ana Mendieta para su clase en la escuela Kirkwood. Foto y cortesiaHelen (McGreev) Hoff

Ana Mendieta, Sin título (figura velada en un nicho, Cuilapan, Oaxaca), 1973

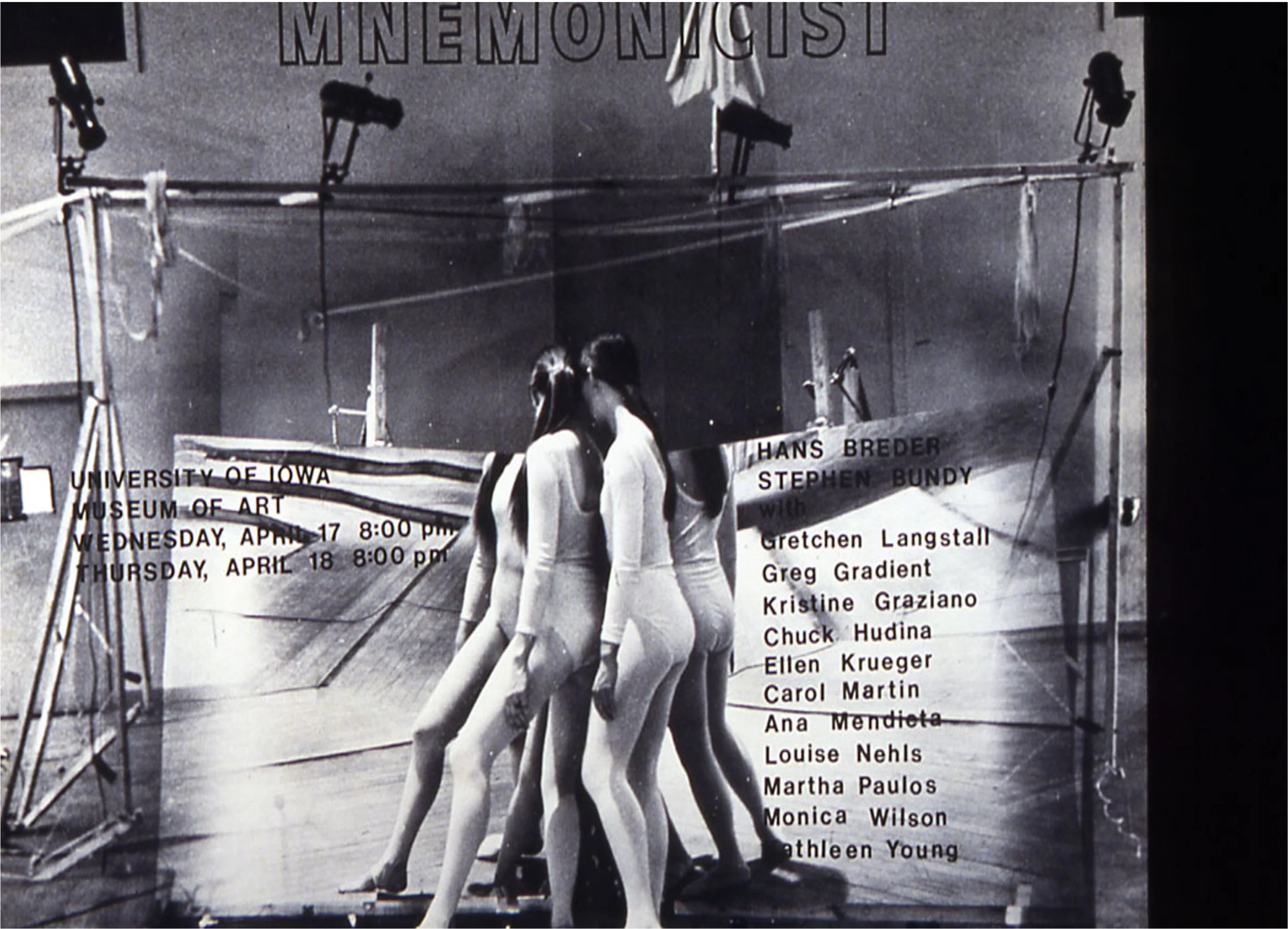

Hans Breder, Mnemonicist, CNPA, 1974

Mendieta used her body to create “narrative environments” addressing: religion, ritual, history, archaeology, art—both past and present—identity, memory, and the connections between art and life. She embraced the notion that the body was both subject and agent of her work, that she could perform an action or ceremony; record or mark the traces of a site or place, or allude to a life cycle, thereby suggesting the transcendence of all things.

Her work found form and encouragement in the Intermedia Program under Hans Breder, the program’s founder and one of the professors who initiated the Center for New Performing Arts (CNPA). Mendieta is one of the dance performers in Breder’s Mnemonicist, conceived for the CNPA in 1974. Although Mendieta began to take Intermedia classes in 1971 when she was still a graduate painting student, she became aware of Breder’s new ideas for an interdisciplinary arts program in early 1970 when they began a romantic relationship that lasted for ten years. Intermedia emphasized an interdisciplinary approach to art-making, which included an exploration of unconventional materials and supports such as Plexiglas constructions, structured canvases, painted sculptures, light projection on sculptures, and other combinations of materials and surfaces. Breder also emphasized the use of kinetic and environmental elements. Students from different areas in studio art, performing arts (dance, theater, music), writing, and film were encouraged to integrate aspects of their individual disciplines into the development of more conceptual forms of expression. For several years, from 1970 through 1975, the Intermedia Program partnered with the CNPA, which was also officially inaugurated in the fall of 1970. The CNPA developed a singularly innovative interdisciplinary arts program supported by the Rockefeller Foundation. During those five years, avant-garde artists and performers were invited to the university to teach, perform, and lecture on new developments in the arts.

Marjorie Strider, Scott Burton, and Robert Wilson came to the university in 1970, Willoughby Sharp in 1971. They were among the first to perform or lecture during the first two years of both programs. Strider and Burton were sculptors; Wilson was a director and choreographer of experimental performance and theater; Sharp, a critic and curator. Each of them contributed to Mendieta’s early formation.

Strider and Burton encouraged making art outside the studio in unexpected places. That notion, central to Breder’s teaching as well, became central to Mendieta’s practice beginning in 1973.

Scott Burton, Furniture Landscape, 1970

This is Burton’s Furniture Landscape, a three-dimensional sculpture-performance-installation that he presented in a wooded area of the Iowa campus. Truckloads of faculty, students, and Iowa residents went out in the woods to look for the work, which was partially camouflaged by the surrounding vegetation. I think that the hide-and-seek quality of Burton’s work had a lasting effect on Mendieta.

Ana Mendieta, Sin título (“Suitcase among the rocks”), de la Rape Scene, April 1973

Ana Mendieta, Colchones (Mattresses), October 1973

These are a few examples of her outdoor work, which she hoped passersby would chance upon and take notice. And if that happened, a passerby would certainly wonder about the work’s form, location, and meaning.

Ana Mendieta, Las esculturas en espuma de poliuretano (Foam Sculptures), Jan. 1972

Marjorie Strider’s polyurethane foam sculptures became a model for Intermedia students who wanted to try making sculpture in that medium. With a special machine, obtained by Breder, Mendieta did a series of foam sculpture attached to canvases that she exhibited in early 1972 at the end of her first Intermedia course. Her work with polyurethane foam was short-lived, but her experiences with it seemed to have made her aware of the importance of process and timein the making of art.

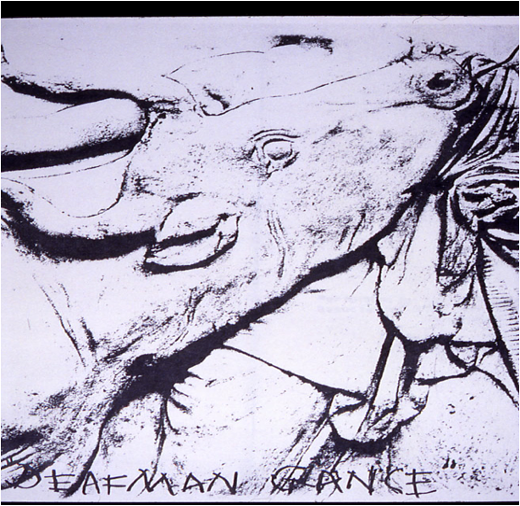

Robert Wilson, portada para Deafman Glance, 1970

In fall 1970 the CNPA invited Robert Wilson as an artist in residence to produce Handbill and Deafman Glance. Mendieta performed in both. Wilson’s living quarters became an intermedia community where students, faculty, Iowa City residents, and occasionally performers from New York discussed how artwork could bridge the boundaries between art and life. His daily workshops in body awareness and movement provided several important learning experiences: one, they stressed the importance of the body in creating a scene, a notion she exploited to its limits; two, they affirmed the necessity of spontaneity within a well-rehearsed framework; and three, they taught the importance of being in control of one’s body while performing—an action that required delicacy, balance, and concentration. These ideas were reinforced by Breder as well as by other artists who taught or lectured in both programs.

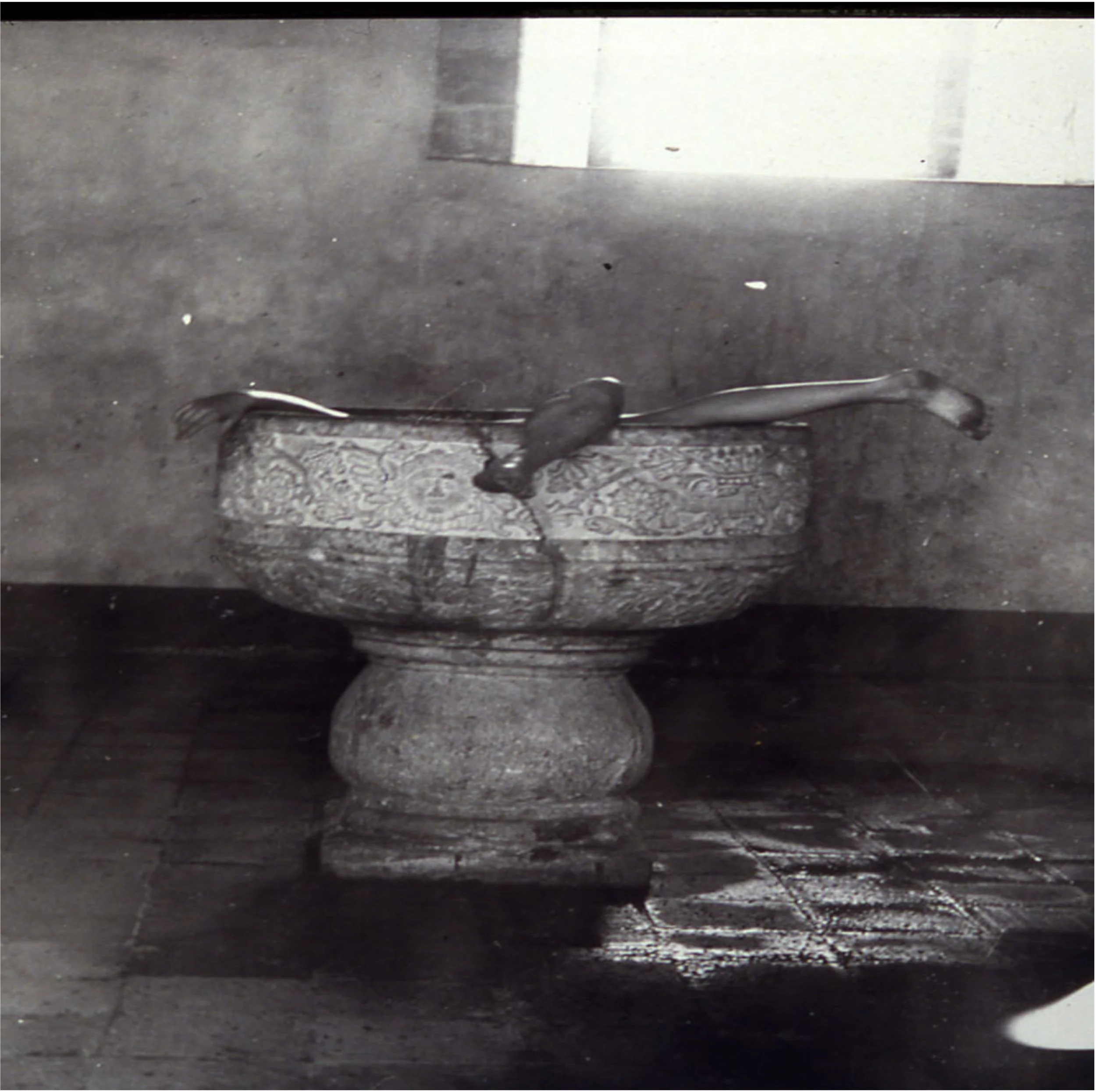

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Body Piece in Baptismal Font), (artista en la fuente bautismal en la iglesia en Cuilapan, Oaxaca, Mexico), verano 1974. Photo courtesy Hans Breder

Hans Breder, Body Sculpture (modelo, espesos, columnas en el aire libre de patio), iglesia Cuilapan, Oaxaca, Mexico, 1973. Foto y cortesia Hans Breder

Ana Mendieta, Sin título (Ape Piece), Junio 1975 Performance en All Iowa Fair, Cedar Rapids, Iowa

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Ape Piece), June 1975, Performance en All Iowa Fair, Cedar Rapids, Iowa

Mendieta adopted these ideas, as noted in two very different works, Body Piece in Baptismal Font (summer 1974) and Ape Piece (June 1975). In the former, her body sculpture was performed in an unused baptismal font in the sixteenth-century Dominican Cuilapan church outside Oaxaca, Mexico. The church complex was built on the site of a former Zapotec temple. In conceptualizing this body sculpture, the artist referenced multiple sources: the sacrament of baptism in the Catholic Church; the forced conversion of native peoples by the Spanish; and the kinectic body sculptures of Breder, who photographed live models with mirrors in another area of the same church.

In Ape Piece, performed at the “All Iowa Fair” in Cedar Rapids in June 1975, Mendieta developed her version of a gorilla parody common in circus sideshows in which a person dressed as a gorilla moves through the aisles under the big top. Mendieta, along with Ann Zerkel audited Breder’s summer-school course in which the students were assigned to do work at the fair.

Zerkel, assisted Mendieta in dressing for the ape role. Mendieta had finished all but one requirement, and therefore audited the course. However, she continued attending Intermedia classes because they gave her the opportunity to use the studio, to show her work to graduates in the program, and to further her practice, which was evolving outside the formal curriculum. Mendieta’s Ape Piece piece recalls Joseph Beuys’s, I Like America and America Likes Me (1974), in which the felt-wrapped artist lived with a coyote in a cage for several days in the Rene Block Gallery in New York City.

Joseph Beuys, I Like America and America Likes Me, 1974

The critic Willoughby Sharp came to the university to lecture in spring 1971 on the most recent developments in body art, a term he coined in his first magazine article “Body Works” that appeared in Avalanche in fall 1970. The magazine was a critical vehicle for disseminating new directions in the various forms of body, conceptual, and minimalist art. Students became very familiar with the contents of the magazine in the Intermedia studio, where copies were available (1970-1976). Sharp showed videos and lectured on the work of Vito Acconci, Bruce Nauman, Dennis Oppenheim, William Wegman, among many other innovating artists.

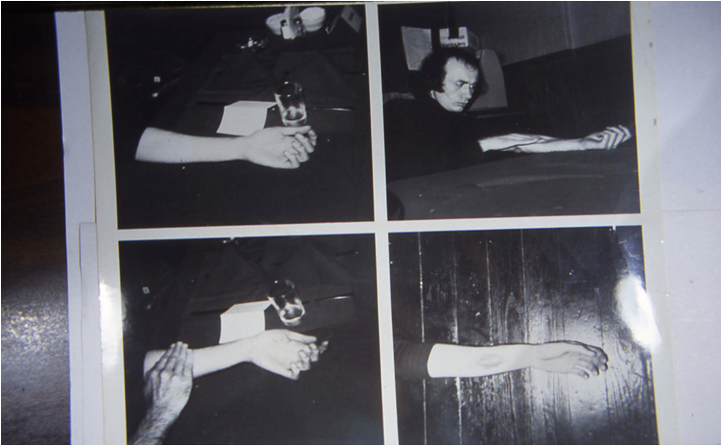

Vito Acconi, Rubbing Piece, 1970

Franklyn Miller, a professor of film and video at the university and a collaborator in the CNPA performances, commented that Sharp was an “important vector” in disseminating knowledge of some of the recent artistic modes. He also provided the language and critical framework with which the students—and faculty as well—could articulate their visual explorations. The work Sharp showed, in conjunction with the discussions that took place in the Intermedia studio, inspired Mendieta with new expressive possibilities for using her body as a performative medium. After Sharp’s visit, Breder focused on the body as an agent in art. In Rubbing Piece of 1970, Acconci rubbed his left forearm for an hour until he had a sore. The notion of inflicting pain or causing discomfort by pushing the limits of the body was an objective of many early performance works. Mendieta did not subscribe to that aspect of practice.

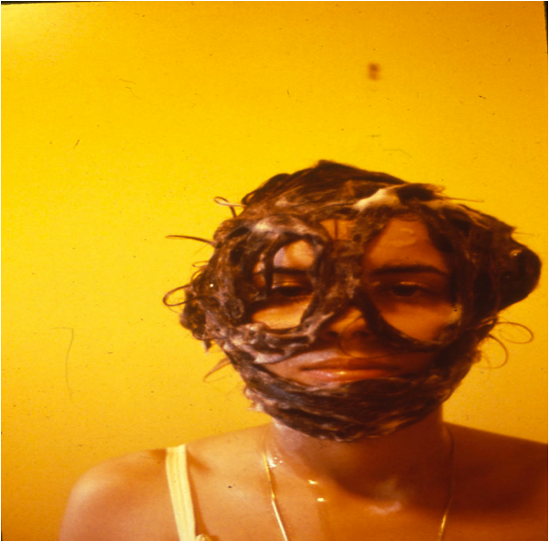

Ana Mendieta, Facial Cosmetic Variations (face covered w/ hair & suds), 1972

Ana Mendieta, Facial Cosmetic Variations (face covered w/ hair & suds), 1972

Marcel Duchamp with Shaving Lather, a study for Monte Carlo Bond, 1924

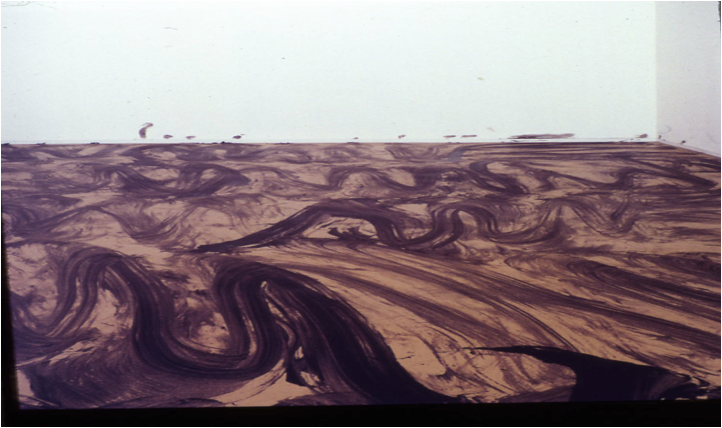

Janine Antoni, Loving Care, 1992-95

Mendieta’s Facial Cosmetic Variations was among her first performative works documented in the Intermedia studio in spring 1972. One of the artist’s objectives in this series was to perform a piece in which she could re-present her everyday look to get a different sense of self. In this frame Mendieta alters her appearance by forming a weblike mass over her face, and in another her hair is twisted on top of her head. Intermedia students One of the artist’s objectives in this series was to perform a piece in which she could re-present her everyday look to get a different sense of self. In this frame Mendieta alters her appearance by forming a weblike mass over her face, and in another her hair is twisted on top of her head. Intermedia students were discussing the work and ideas ofMarcel Duchamp. Mendieta’s series recalls Man Ray’s Marcel Duchamp with Shaving Lather, a study for Monte Carlo Bond. Facial Cosmetic Variations also calls to mind the later piece, Loving Care by Janine Antoni, a performance in which the artist mopped the gallery floor with her dye-soaked hair, conjuring images of gestural painting, a la Jackson Pollock.

Marcel Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q, 1919

From spring 1972 through 1973, Mendieta continued her experimentation with body change. In her Facial Hair Transplants, she transferred the facial hair of a friend, Morty Sklar, onto her own face in a slow, deliberate ritual, suggesting a gender transformation, similar to Duchamp’s famous L.H.O.O.Q whose image of the Mona Lisa he altered by adding a moustache and beard. Because Duchamp radically transformed the appearance of the enigmatic woman, he was an important model for Mendieta, who cited him in her master’s thesis. Body art was about creating new identities, however temporarily.

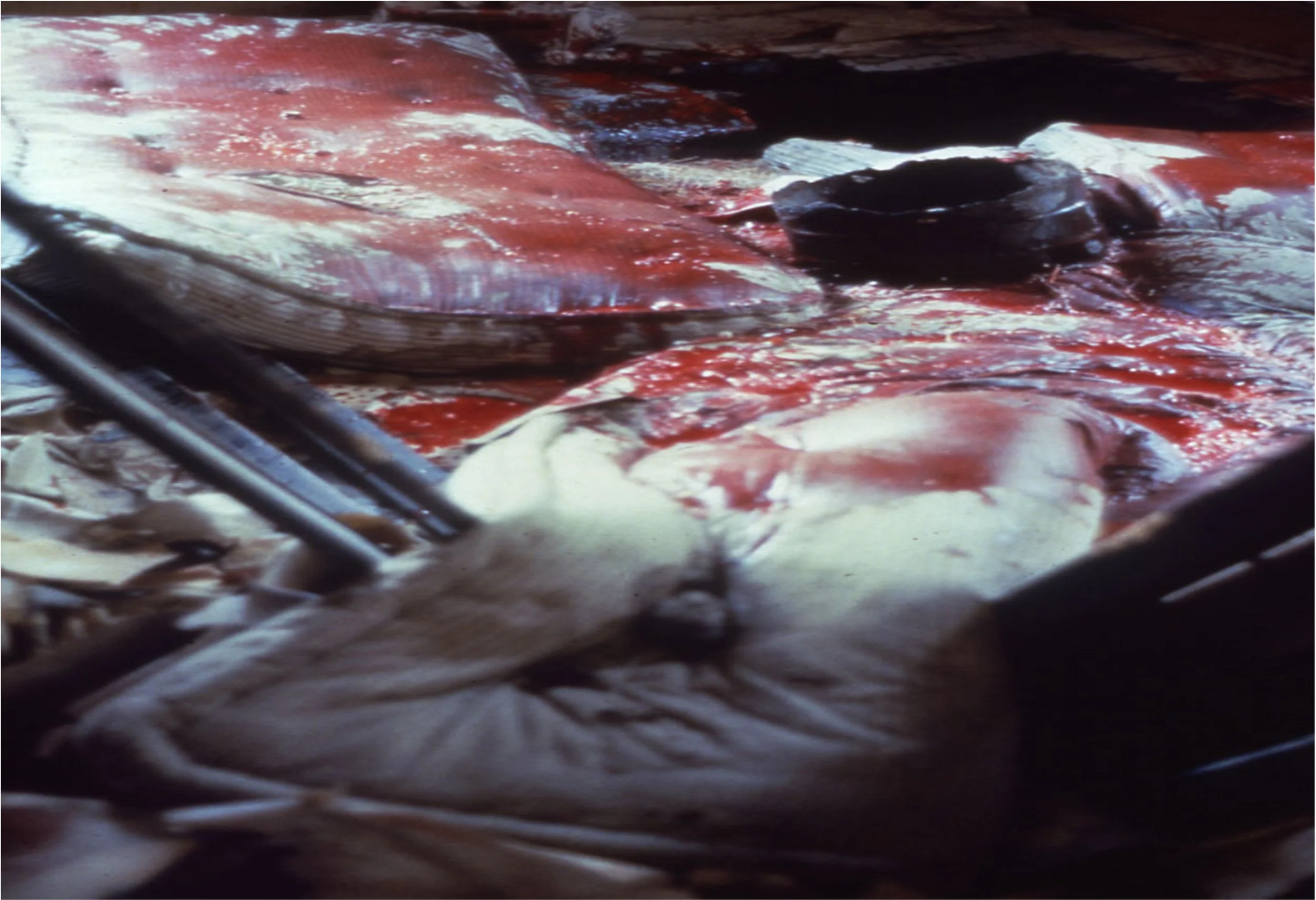

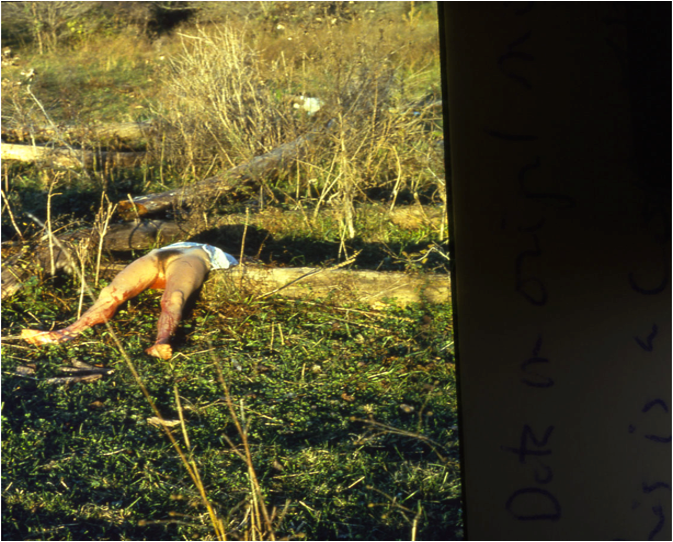

Ana Mendieta, Rape Series (the rape-murder in a wooded, hidden in the underbrush), 1973

1973 marked a period of transition. Mendieta finished most of her formal coursework for her master of fine arts degree, although she continued attending Intermedia classes. She began producing site-specific work, participated in CNPA programs, and began working in Mexico. In 1973 she did a year-long exploration on the subject of rape and violence. This is one of thirty-five shots featuring different positions of Mendieta performing a rape-murder in a private wooded area in front of the camera. She combined ideas from various sources: the actualcampus murder of a female student, Scott Burton’s site-specific Furniture Landscape, and Duchamp’s view of a naked woman through a peephole in Etant donnée.

Marcel Duchamp, Etant Donnés (interior), 1946-1966

Ana Mendieta, Rape Series (the rape-murder In a wooded area), Oct. 1973

In viewing the slides in the sequence they were shot, one senses the detailed planning of a crime that no one discovered, because it was staged privately. But in creating the performance piece, Mendieta relied on fact, fiction, and theatrical know-how. The work is characteristic of the way she had begun to instill the element of surprise into her work wherever it was produced. Mendieta's performance work concerning rape places her in the vanguard of contemporary women artists such as Suzanne Lacy who did several works on that subject. Lacy's artist's book Rape Is of 1972 is a textual chronicle defining physical violations.

Susanne Lacy, In Mourning and in Rage, 1977

In Mourning and in Rage is a performance piece that features women dressed in black robes silently protesting in front of a public building. Neither, however, graphically alluded to the physical violence implicit in Mendieta’s tableau.

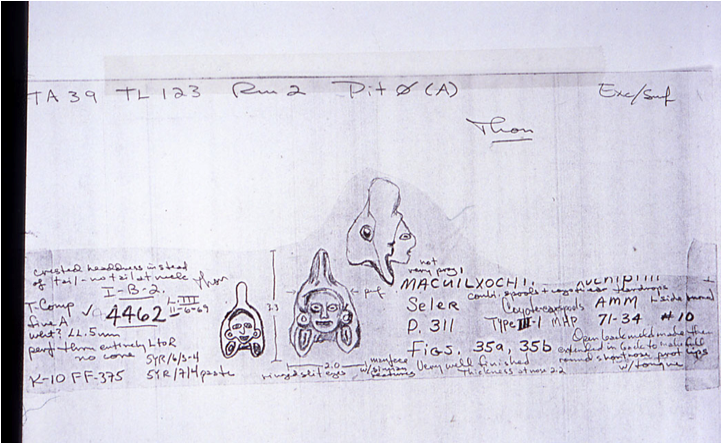

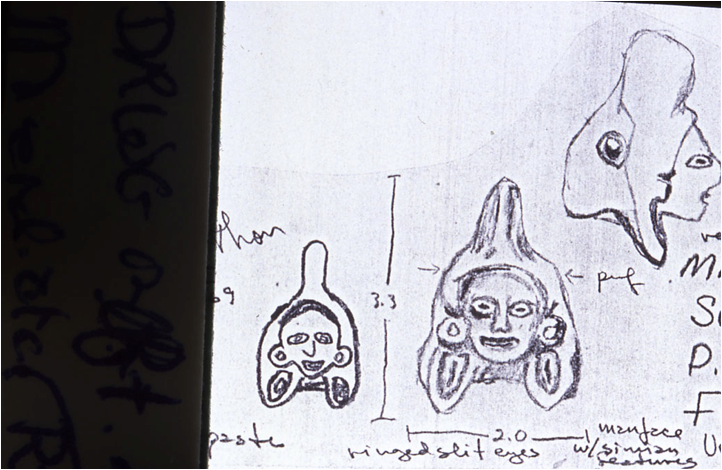

Mendieta & Cynthia Otis Charlton, Catalogue card TA 39 TL 123. Drwgon left of Macuilxochitl by AM, 1971; two drwgs on rt by Cynthia Otis Charlton, 1978

Ana Mendieta, “Idolo/ Idol” II, c. 1972

That same fall Mendieta directed “Freeze,” a movement piece with her fifth- and sixth-grade art students from the Sabin school, in a CNPA performance. Mendieta periodically called out “freeze,” at which point each child stopped and held his or her position for a brief time without moving. One of the ideas behind the piece was to capture a series of natural body movements while communicating the notion of the body as a sculptural form. In the program Mendieta wrote a brochure in which she set forth her conceptual approach to art-making, stating that time, process, and ephemerality are elements of artistic creation.

Mendieta’s Mexican experiences were first acquired in her undergraduate coursework. She initially went to Mexico in summer 1971 to do Field Research in Archaeology at San Juan Teotihuacán. She worked under Professor Thomas Charlton who taught her how to gather and study late Aztec (1400–1520) and very early colonial artifacts. She became the first of his students to begin to establish a system of typologies for Aztec deities, recording her findings on catalogue cards, tally sheets, and in a report that her professor kept as part of his working archives. She returned to Mexico in summer 1973 with Breder who led the first of many summer-school classes to do site-specific work there. He encouraged his students to capture the “magic” of the place, and certainly Mendieta sensed the aura of the archaeological sites, churches, graveyards, and landscape where she developed a brilliant body of work. She became convinced of the superiority of the art and culture of Pre-Colombian peoples, a point she made in writings, interviews, and lectures throughout her life.

Ana Mendieta, Imagen de Yagul, 1973

In Image from Yagul the artist lays nude in a shallow grave near that archaeological site. Following her directions, Breder placed white flowers over her to cover her body. More importantly, however, the flowers symbolized life, reinforcing the Pre-Columbian belief that the soul or life force lives on in the afterlife. This was a pivotal piece in which she established her own connections with Pre-Columbian culture in her body performances: it looked back on her paintings with Mesoamerican iconography and forward to conceptual work that explored Pre-Columbian art and history.

Ana Mendieta, Sin título (Labyrinth Blood Imprint) Yagul, 1973

Untitled (Laberinth Blood Imprint) of 1974 was executed on the floor of the Palace of the Six Patios in Yagul when the summer school class was at the site. Having planned the work ahead of time, she was able to execute it quickly. Mendieta stretched out on the floor with uplifted arms and, as Breder traced her outline, created a motif in the form of a prehistoric goddess, an image that would soon attract critical feminist attention. Mendieta then filled in the silueta with cow’s blood that she had brought to the site and managed to step aside before a guard swept it away. The image, together with the one in the shallow grave, was the beginning of her silueta series. The artist’s body was the central vehicle for her narrative. By means of her silueta, she inserted herself into the history of a given place, embodying the notion of the trace as the marker of a former presence.

Ana Mendieta, Burial Pyramid, 1974

Dennis Oppenheim, Rocked Hand, 1970

Burial Pyramid, also done at Yagul that same summer, was the artist’s first earth-body-work. The film documents her slow emergence from beneath the rocks. In addition to incorporating the site as part of her art, she responded to the history of the region, which was still under excavation. Burial Pyramid echoes some of the strategies that Dennis Oppenheim employed in Rocked Hand of 1970, a performative earthwork fairly well known at the time. The film showed him covering one of his hands with rocks for the purpose of blending with the surrounding landscape. Mendieta adopted a similar concept but was more interested in realizing a spiritual fusion with the earth at the ancient Zapotec site.

Ana Mendieta, Silueta Tehuna, 1976

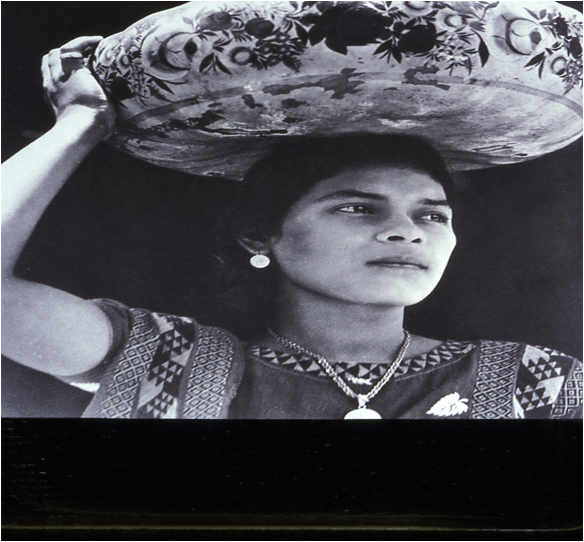

Tina Modotti, Tehuana, 1929

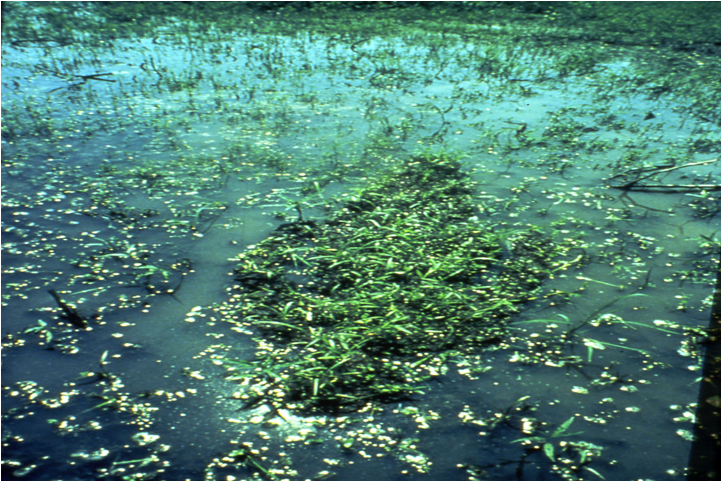

In addition to working at archaeological sites or the Cuilapan church complex, the artist did earth-body-sculptures in the Mexican landscape. Silueta Tehuana of 1976 typifies the way Mendieta rearranged natural vegetation to form an image (silueta) that was fashioned in the size of her own body. The objective was to give a human form to nature, thereby affirming that nature is alive, reproductive, and eternal. In drawing on history, the title refers to the matriarchal society of Tehuana women, who come from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, an area Mendieta and Breder visited every summer. The artist not only drew on local history for subject matter but also referred to earlier 20th-century Mexican art history by the title of her work: Tehuana women had often been the subject of paintings by Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, as well as by the photographers Hugo Brehme and Tina Modotti, all of whose work Mendieta knew well.

Ana Mendieta, Silueta de cenizas, 1975

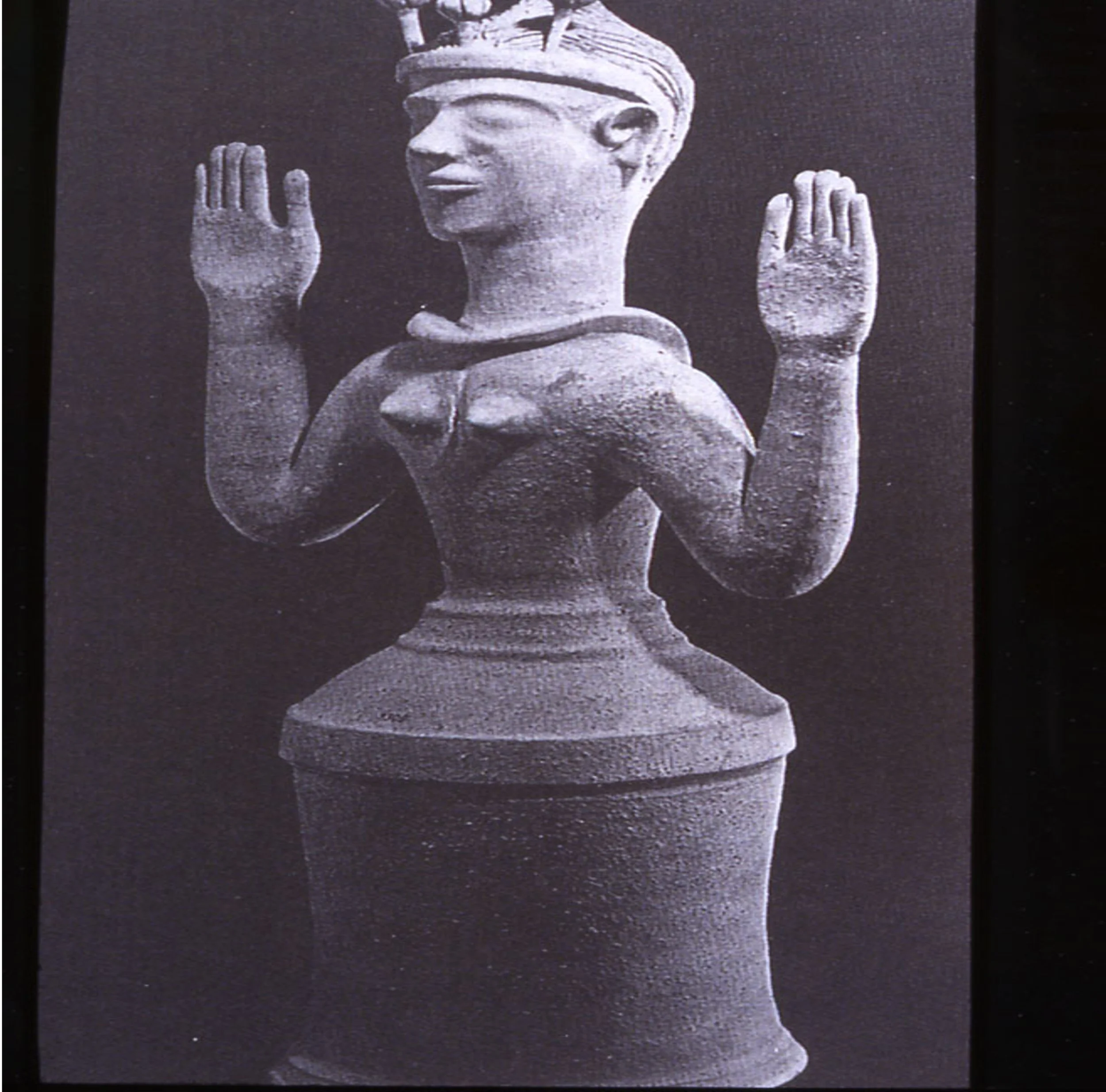

Prob. Late Minoan Fertility Figure, c. 1350 BC

In Iowa, especially from 1975 at the end of the Rockefeller Foundation’s support for the CNPA, Mendieta began working extensively outdoors along the Iowa River on a professor friend’s property, or in or near Old Man’s Creek on private property to which she and Breder had access. Silueta de cenizas is one of her early burning pieces that features the artist with her arms in an upraised position, a motif that she knew from prehistoric mother earth figures, such as this Minoan fertility figure or perhaps from a large painted pictograph on the face of a cliff, at the nearby archaeological site of Caballito Blanco near Yagul. Unlike the monumental earthwork of Smithson, Mendieta’s personal idiom was one that left nature intact; it depended on an intimate, spontaneous selection of natural elements, and was thus closer to Richard Long’s marks in the landscape.

In Genesis Buried in Mud of 1975, a film in this exhibition, the artist had herself covered with mud. The innovative performative action drew on the ideas in Burial Pyramid where she emerged from rocks. However, in Genesis Buried in Mud, the viewer sees the earth moving ever so slightly due to the artist’s breathing beneath the ground. Through the use of the mother earth figure with the uplifted arms and the earth itself, Mendiata expressed the phenomenon that nature is a life force.

Ana Mendieta, Tree of Life (Arból de la vida), 1976

Ana Mendieta, Tree of Life series (on fallen tree), 1976

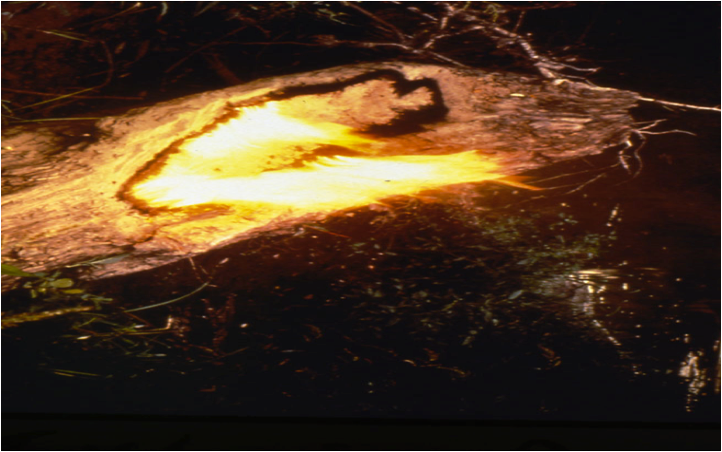

Ana Mendieta, Sin título (silueta on burning tree), 1977

Tree of Life features the artist with arms upraised, covered in mud, standing against a tree, appearing Daphne-like. In uniting with the tree, the fusion of human and nature’s forms become almost imperceptible—perhaps an oblique reference to biblical creation: God formed the earth and then formed man and woman. During the same outing, the artist did a similar untitled piece from the Tree of Life series in which she recalled memories of her homeland. She placed her camouflaged, mud-covered body in a felled tree, melding it with nature. In her sketchbook she explained her intentions to do a piece inspired by her memories of the Cuban landscape by recalling the shape of the hills known as the Pan de Matanzas (near the city of Matanzas), which were in the shape of a reclining woman. This shot was taken when Mendieta was covering herself with mud in preparation for works in this series.

Ana Mendieta, Sin título (silueta de flores rojas, Mexico), 1976

Ana Mendieta, Sin título (silueta de flores rojas, Mexico), 1976

By the time Mendieta graduated from the Intermedia Program (May 1977), she had evolved earth-body-work utilizing all of nature’s elements: — air, earth, water, and fire, the latter element used to burn a human form into a tree trunk (a work in the Des Moines Art Center’s Collection). In the film Ocean Bird Washup the artist ran along the shoreline in La Ventosa; She rearranged natural materials such as red flowers (Untitled, Silueta Series, Mexico, 1976), which were washed up by the tides, symbolizing the ebb and flow of life.

Ana Mendieta, Sin título (Momia en Iowa), 1975

Christo, Package, 1961

Mendieta explored Mesoamerican subjects in her Iowa work. This untitled piece of 1975 had multivalent sources: wrapped in strips of wet plaster gauze while crouching in a fetal position, the artist attempted to replicate mummies she had photographed in Mexico. In terms of contemporary art sources, the piece both recalls Christo’s wrapped objects and George Segal’s white plaster gauze figures. Graduate students in Intermedia were very familiar with these artists as well as with the different modes artists used in wrapping their models.

Ana Mendieta, Ix-Chell, 1977

Mendieta Catalogue Card Macuilxochitl-Xochipilli, 1971.

For her MFA thesis in May 1977, Mendieta did a series of body sculptures titled Ix-Chell. Wrapped in strips of black cloth to look like a mummy, she referenced the Maya goddess of weaving, medicine, and childbirth. Although Mendieta had been familiar with Mesoamerican deities for many years, as noted on her catalogue card for Xochipilli, Ix-Chell was the first to identify by name a specific deity. The work was critically noticed by feminist art writers who had begun to write about her. The artist’s practice of identifying Pre-Columbian as well as Afro-Cuban deities was one she would further advance after her move to New York in 1978 and subsequently in her work in Miami and Cuba.

Ana Mendieta, Sin título (floating grass island in water), Iowa, 1978

Ana Mendieta, Silueta Series (yellow flowers in grass), 1979

Richard Long, Untitled, 1970

Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty, 1970

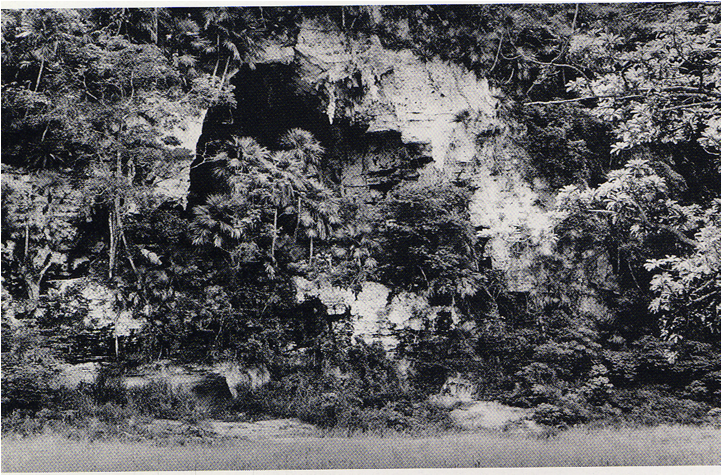

Visión general de Oaxaca

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (figura tallada en una colina, Oaxaca), 1980

In 1978, she moved to New York, joined the A.I.R. Gallery and began to establish herself among a relatively small but important group of women artists whose feminist stances aimed to challenge the artistic practices dominated by men in the mainstream art world at the time. As noted in these images, Mendieta continued producing outdoor earth-body work in Iowa on frequent return visits in 1978 and 1979. During her last trip to Mexico prior to her breakup with her lover Hans Breder, she carved these figures into the riverbanks. They were the forerunners of carved rock pieces in Varadero and Jaruco, Cuba the following year.

Escaleras de Jaruco, Cuba, 1981

Cueva del Aguila, Escaleras de Jaruco, Cuba, 1981

In early 1980, Mendieta went back to Cuba for the first time since 1962. She traveled under the auspices of the Circle of Cuban Culture (Círculo de Cultura Cubana), an organization founded by Cuban exiles to promote cultural exchange and relations between Cuba and the United States. She was thrilled to be reunited with her grandparents and relatives who lived in Havana, Varadero, and Cárdenas. [She also visited Santiago de Cuba, Camaguey, Trinidad, and Cienfuegos.] As tokens of her native land, she brought back earth from Cuba and sand from Varadero and kept them in her NY apt. Mendieta receives a John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship and an NEA grant.

Ana Mendieta, Sin título (Guabancex, deidad del viento), Escaleras de Jaruco, Cuba, 1981

Ana Mendieta, Guanaroca (Primera mujer), Escaleras de Jaruco, Cuba, 1981

The Rupestrian Series was a large-scale outdoor installation of the pre-Hispanic goddess images carved into the rocks in the mountainous park of Jaruco, outside of Havana. They attest to the artist’s lifetime passion for Pre-Columbian history and cultures. Although the Cuban government authorized her work at Jaruco, Mendieta financed it with funds from a John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship award. That grant together with funds from an NEA grant enabled her to develop the photographs in a larger scale, which she exhibited at her first solo show at the A.I.R. Gallery in November ‘81.

Ana Mendieta, Isla, 1981

Ana Mendieta, Sin título (Ochún, deidad del agua), Miami, 1981

During Mendieta’s trips she considered staying in Cuba and working as an artist, but she realized that New York was her primary site for the production of her artwork. As she negotiated two cultures, she was keenly aware that Cuba—and by extension her family, language, and culture —defined her. Between a series of trips to Cuba from 1981 to 1983, she titled some of her sculptures in Spanish as a way of referring to her Cuban identity in her artistic production. Isla (Island) of 1981 is one of several examples.

Ana Mendieta, Fetiche Ceiba, 1982

Mendieta began working in Miami, a city that replaced Oaxaca and other Mexican locations. Ochún and the Ceiba Fetish are among several important works she did. Ochún, a deity associated with water and beauty in Afro-Cuban Santería, was sculpted in sand in Key Biscayne. The ephemeral piece relates to a number of water pieces the artist had done from the mid-70s in both Mexico and Iowa. Because Ochún was oriented toward Cuba, it is iconographically closer to Isla in that it is a referent to the island nation.

Mendieta made a silueta of hair on the tree in Cuban Memorial Park, in the heart of Miami’s Little Havana. The actual tree has since become a devotional place used by local residents, who have over time continued to add reverential objects to it.

Ana Mendieta, Arbitra, Hartford, Conn., 1982

Finally, we might look at three innovative directions. This is Arbitra (Witness), a tree trunk with her signature silueta burned into it, commissioned by the Hartford Art School and Real Art Ways in Hartford. Mendieta thought gunpowder gave her works a visual charge; it seemed literally and metaphorically to imbue the work with power. In addition gunpowder created fire, the third element with which Mendieta worked. This work signaled a conceptual change in the artist’s desire to make public works that had greater permanence. Incidentally, this piece was thrown away by maintenance people who did not realize it was a work of art!

Ana Mendieta, Sin título (Totem Grove Series), 1984

In ’83 Mendieta won the Rome Prize, which provided her with a studio at the American Academy in Rome. After her residency ended in mid-1984, she rented an apartment and studio on the American Academy grounds where she continued living and working between trips back to the States. Four untitled freestanding sculptures were found in her studio after her death in Sept. ’85. She had enlisted the assistance of her colleague Nunzio Bulla who was also making sculptures of charred wood at the time she acquired the tree trunks. He in turn introduced her to an art professor, sculptor, and skilled carver who worked with Mendieta to shape several tree trunks. She had accepted an offer to do a commission for the MacArthur Park Public Art Program for the Otis Art Institute of Parsons School of Design in Los Angeles. She wrote about the project, saying that it would consist of seven wooden totem sculptures titled La Jungla, after Wifredo Lam’s famous painting in the MoMA collection. It is unclear, however, if these four tree sculptures were the beginning of that group or whether she had finished this sculptural group or whether each was considered an independent sculpture.

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (design on leaf), 1983

Although Mendieta’s life was cut short at age 36, her legacy is long. She discovered a mode to vivify nature (read life) by utilizing her own body or its silueta. In retaining the traditional narrative power of the female figure, she moved across historical periods, traversed cultural contexts, and evolved ephemeral and permanent work that imparted a sense of universal energy. She defined an artistic practice, which depended in part on her linkage to the eternal flow of history as well as to nature—the source and repository of life.