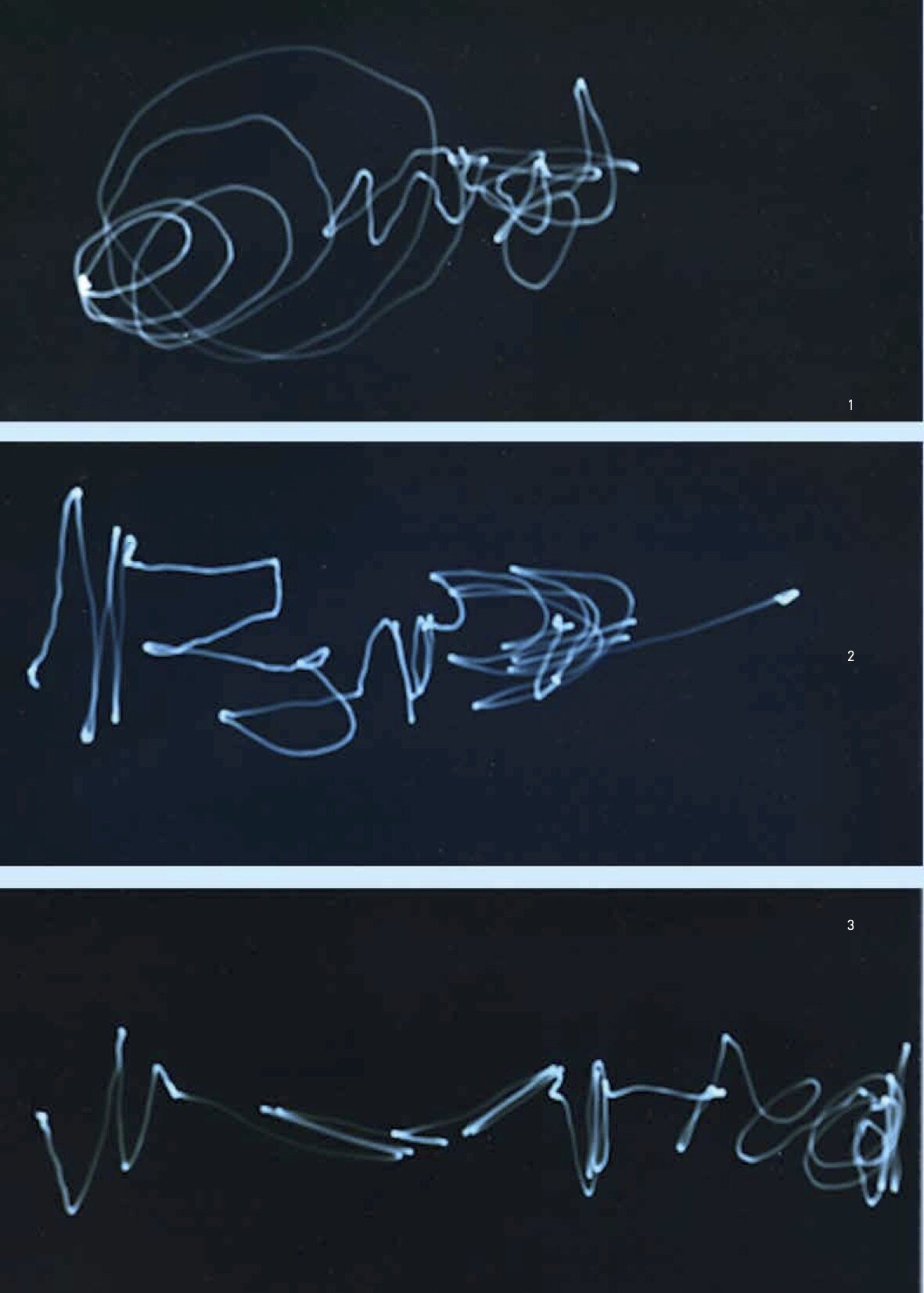

Lunar Writing 1 (1001, 1002, 1003), 1974, 16 blue toned black and white photographs mounted on museum board, 6.25 x 9.25 inches each.

Courtesy of the artist and Henrique Faria New York & Buenos Aires.

Lunar Writing 1 (1001, 1002, 1003), 1974, 16 fotografías blanco y negro viradas al azul montadas sobre tableros de exposición, de 16 x 24 centímetros cada una. Por cortesía del artista y de Henrique Faria, Nueva York y Buenos Aires.

IN CONVERSATION with LEANDRO KATZ

The visual artist, writer, and filmmaker spoke with Julia P. Herzberg for Arte al Día about his work process, his interest in photography and its boundaries.

(Spanish text follows.)

Since the late 1980s, I have had the extraordinary experience of working with Leandro Katz, who creates art across the disciplines of photography, artist’s books, objects, installations, and films. After the artist returned to Buenos Aires from New York in 2006, I visited his studio annually. In February of 2015, I first saw the artist’s series Lunar Writing (1974). I proposed an article on those incredibly beautiful photographs, which had not yet been written about. Following a series of written communications, and a recorded conversation in February in 2016 in Buenos Aires, we focused on “writing with light” in the Lunar Writing series, and on two other works. The following conversation illuminates some of the artist’s thoughts.

Julia P. Herzberg: How did you conceive of the notion of writing with light?

Leandro Katz: I have always been interested in experimenting with photography and going to the edges, where I try things that have not been done or have not been recommended beyond the manufacturers’ specifications. When I had the idea of photographing the moon, the challenge was to figure out all of the technical aspects before proceeding. As I acquired technical control of night photography, it occurred to me that I could do different things such as expose film in ways that tested the technical limitations of the medium.

I discovered several things. When filming the moon with time-lapse devices, I realized there was something very peculiar going on with the film emulsion, as clouds and haze were covering it momentarily. The process was comparable to the technique of solarization, which briefly exposes a negative in the darkroom to a flash of light. Something similar was taking place in real time due to the absence/ presence of light. The film emulsion was reacting as it was being exposed to the rays of moonlight, expanding the mysterious behavior of the medium. Results such as these, with motion picture film, gave me the idea of writing words with a still camera.

Lunar Sentence II, 1978, 264 silver gelatin prints, 7 x 5 in. each, in twelve panels mounted on museum board in two sections of six panels; overall dimensions 98 x 76 in. for each section. Photograph by Robert Schweitzer. Courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Lunar Sentence II, 1978, 264 copias a la gelatina de plata, 18 x 13 cm. cada una, montadas sobre cartón de museo en dos secciones de seis paneles; dimensión general de cada sección: 250 x 195 cm. Fotografía de Robert Schweitzer.

Cortesía del artista y el Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Nueva York.

JPH: And that’s how Lunar Writing I and Lunar Writing II developed? Did you hold the camera outside your window?

LK: No, I had a terrace that literally became a workspace with tripods and a table. I waited for nights with clear skies. I consulted the Farmer’s Calendar and the meteorological services to know the weather conditions of particular nights. When I was ready with my calculations, I set up the camera and film and photographed the moon. As you know, I also made four films of the moon: Twelve Moons (and 365 Sunsets), 1976; Moonshots, 1976; Moon Notes, 1980; and The Judas Window, 1982. The thought of photographing the moon with a hand-held camera gave me the idea of writing, which is a paradoxical attempt. It is like moving a sheet of paper over a fixed pencil pointing at you.

JPH: Did you have certain words in mind?

LK: I don’t remember what I wrote because writing became like a magic spell, an invocation. I don’t even remember to whom I was writing, but it was probably a love letter. I took the camera and wrote a verse or prayer or letter by simply moving the camera over the image of the moon.

JPH: By using the camera to write, the sky itself became like a page.

LK: Yes, the night itself. For me writing was a ritual, an intimate action that I sent to the universe. Writing with moonlight may seem as an innocent act but at the same time, it was a very calculated one, technically speaking. You had to know the film’s specifications, the shutter speed, and the intensity of the moon light. In other words, there is an aspect in all photography of extreme calculation, even though it may be an impulse filled with personal emotion.

JPH: When you did Lunar Writings I, for example, did you expose all the frames in one shooting, in one night? Or did you shoot the moon over a series of nights?

LK: All in one night and in a single film roll. For each frame, it was a different word or set of words. I opened the shutter, moved the camera to write across the frame, closed the shutter, advanced the film, and then wrote on the next frame, and so on. I probably used an average of sixteen to twenty frames for the two writing attempts. There is another step in the process. After the film was developed and the results approved, I made black- and-white prints, and then I subjected the resulting prints to a further chemical process called blue toning, in which you dip the dry print in a chemical solution that replaces the black silver nitrate emulsion for blue tone color particles.

JPH: That’s why we see the abstract, linear, and gestural lines of the moon in a blue color?

Yes, all the colors are bluish including the lowlights and the highlights. Everything that is silver is replaced by this chemical action.

Night Flights, A Diary #13, 1976, 15 chromogenic prints, 12 x 17 in. each. Courtesy of the artist and Pelusa Borthwick .

Night Flights, A Diary #13, 1976, 15 copias cromogénicas, 20 x 43 cm. cada una. Cortesía del artista y de Pelusa Borthwick.

JPH: Were there any artists writing with a camera that you were aware of? Were there any precedents that were of interest to you in either modernist photography or perhaps in contemporary work?

LK: Not really. I consider myself a kind of lone wolf. If I see that something has been done, then I am not interested in pursuing it. When something occurs to me, it has to do with the more metaphysical aspects of the medium. What is photography? What is a camera? What is black and white? How do we see things, and so forth? I am not interested in a dialogue with other artists. I am interested in a dialogue with the technology, with invention. The idea of the avant-garde, of doing something that hasn’t been done before is important to me.

JPH: Lunar Writing I and Lunar Writing II of 1974 were completed a few years prior to the now iconic Lunar Alphabets (1978-1980). What other works did you do by writing with the camera? Do you see those as antecedents to Lunar Alphabets?

LK: Well, yes, there were several years in between these experiments before I made the first Lunar Alphabet in 1978. In making that work, I collected twenty-seven transitions of the moon taken during many nights until the right shape of the crescent moon was perfect for a particular character of the alphabet. Some images of the moon had to be redone, which meant that I had to wait another lunar month before I could catch the particular angle that I needed. In other words, even though these works, Lunar Writing I and Lunar Writings II, were done in 1974, there were films and photographs that I made on my New York terrace and in other places.

JPH: How does Night Flights: A Diary fit into the larger context of Lunar Writing?

LK: The Night Flights: A Diary series belongs to the group of photographs that I did by opening the shutter and photographing something very dark that has some sort of highlight. The idea came when I was flying between New York, Florida, and Texas at night time. I would hold the camera with the shutter open against the airplane window for a few seconds as the plane flew over towns or cities during take off or landing. The film sensitivity and the camera settings recorded a trailing view of the landscape lights that were quite lovely. Night Flights: A Diary suggest the idea of a dairy, of recording something that is taking place on the spot.

JPH: How were you able to get those marvelous colors in the series you did over time?

LK: I think the colors are the result of different light sources. As you know, many cities have different light sources: mercury, sodium, and tungsten lights. They all rendered different colors.

JPH: And these color variations became visible to you once you went into the dark room?

LK: Yes, once the color film was developed. In other words, it is a surprise of photography.

JPH: And I think that Night Flights: A Diary must have been very surprising to you when you first began to develop them. Tell me a little about how you shot a photographic roll.

LK: I was doing one diary in one night in one flight. If I flew again, then I would do another roll. The photographs were not a mixture of different flights but a sequence of shots I took when the airplane was moving and the landscape changing.

JPH: So the works that we have just looked at together were done on a given flight?

LK: Yes, in one evening, in one roll.

JPH: You have done The Vowels, another inventively ludic series of photographs, using a match as a light source to write in the dark. But we will have to leave that discussion for the next time.

This conversation was published in “Leandro Katz,” Arte al Día International 131 (2010): 99-101.

Lunar Writings @ Leandro Katz

LEANDRO KATZ Diálogo

El artista, escritor y realizador argentino conversó con Julia P. Herzberg para Arte al Día International sobre su proceso de trabajo y el interés por la fotografía y sus sinlímites.

Night Flights, A Diary #22, 1976, 15 chromogenic prints, 12 x17 in. each. Courtesy of the artist and Pelusa Borthwick .

Night Flights, A Diary #22, 1976, 15 copias cromogénicas, 20 x 43 cm. cada una. Cortesía del artista y de Pelusa Borthwick.

Desde fines de la década de 1980, disfruto de la extraordinaria experiencia de trabajar junto a Leandro Katz, creador de arte que une las disciplinas de la fotografía, los libros de artista, los objetos, las instalaciones y el cine. El artista regresó a Buenos Aires en 2006, luego de residir un tiempo en Nueva York. Desde entonces, todos los años visito su estudio.. En febrero de 2015, vi por primera vez su serie Lunar Writing [Escritura lunar] (1974). Le propuse escribir un artículo sobre esas fotografías increíblemente hermosas, acerca de las que nadie había escrito aún. Luego de una serie de intercambios escritos, y una conversación grabada en febrero de 2016 en Buenos Aires, nos concentramos en la “escritura con luz” de esa serie y en otras dos obras. El siguiente diálogo ilumina en parte el pensamiento del artista.

Julia P. Herzberg: ¿Cómo imaginaste la noción de escribir con luz?

Leandro Katz: Siempre me interesó experimentar con la fotografía e ir al límite, donde intento hacer cosas que nadie ha hecho o que las especificaciones de los fabricantes recomiendan no hacer. Cuando tuve la idea de fotografiar la luna, el desafío era desentrañar todos los aspectos técnicos antes de proceder. A medida que fui alcanzando el control técnico de la fotografía nocturna, se me ocurrió que podía hacer otras cosas, como por ejemplo exponer la película de modos que pusieran a prueba las limitaciones técnicas del medio. Descubrí varias cosas. Al filmar la luna con dispositivos de time-lapse, advertí que ocurría algo muy particular con la emulsión fotográfica cuando las nubes y la niebla cubrían al satélite momentáneamente. El proceso era comparable a la técnica de la solarización, que consiste en exponer brevemente al negativo a un flash de luz dentro del cuarto oscuro. Algo similar ocurría en tiempo real debido a la ausencia/presencia de luz. La emulsión fotográfica reaccionaba al ser expuesta a los rayos de la luna, expandiendo el misterioso comportamiento del medio. Resultados como este, con película cinematográfica, me dieron la idea de escribir palabras con una cámara fija.

JPH: ¿Y así se produjeron Lunar Writing y Lunar Writing II? ¿Sostuviste la cámara fuera de la ventana?

LK: No, disponía de una terraza que literalmente se convirtió en un espacio de trabajo, con trípodes y una mesa. Esperaba las noches con cielo despejado. Consultaba el Almanaque del Granjero y los servicios meteorológicos para enterarme de las condiciones climáticas en una noche determinada. Una vez que había hecho mis cálculos, montaba la cámara con película y fotografiaba la luna. Como sabes, también hice cuatro películas de la luna: Twelve Moons (and 365 Sunsets) [Doce lunas (y 365 atardeceres)], 1976; Moonshots [Tomas de la luna], 1976; Moon Notes [Notas lunares], 1980, y The Judas Window [La ventana de Judas], 1982. La idea de fotografiar la luna con una cámara de mano me dio la idea de escribir, lo que constituye un intento paradójico, como si intentara hacerlo moviendo una hoja de papel por encima de la punta de un lápiz.

Lunar Sentence II, 1978, 264 silver gelatin prints, 7 x 5 in. each, in twelve panels mounted on museum board in two sections of six panels; overall dimensions 98 x 76 in. for each section. Photograph by Robert Schweitzer. Courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Lunar Sentence II, 1978, 264 copias a la gelatina de plata, 18 x 13 cm. cada una, montadas sobre cartón de museo en dos secciones de seis paneles; dimensión general de cada sección: 250 x 195 cm. Fotografía de Robert Schweitzer. Cortesía del artista y el Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Nueva York.

JPH: ¿Tenías determinadas palabras en mente?

LK: No recuerdo qué escribí porque la escritura se convirtió en algo como un conjuro mágico, una invocación. Ni siquiera recuerdo a quién le escribía, pero probablemente fuera una carta de amor. Tomaba la cámara y escribía un verso, una plegaria o una carta moviendo la cámara sobre la imagen de la luna.

JPH: Al usar la cámara para escribir, el propio cielo se convertía en una hoja de papel.

LK: Sí, la noche misma. Para mí, escribir era un ritual, una acción íntima que yo le enviaba al universo. Escribir con luz de luna puede parecer un acto inocente, pero al mismo tiempo era un acto muy calculado, en términos técnicos. Tenía que conocer las especificaciones de la película, la velocidad de obturación y la intensidad de la luna. En otras palabras, toda fotografía tiene un aspecto de cálculo extremo, aun cuando responda a un impulso lleno de emoción personal.

JPH: Cuando hiciste Lunar Writings I, por ejemplo, ¿expusiste todos los fotogramas en una única sesión, la misma noche? ¿O fotografiaste la luna a lo largo de varias noches?

LK: Todo en una sola noche y con un único rollo de película. Para cada fotograma, usé una palabra o un conjunto de palabras distintas. Abría el obturador, movía la cámara para escribir en el fotograma, cerraba el obturador, hacía correr la película, escribía sobre el fotograma siguiente y así sucesivamente. Para cada intento de escritura, consumí un promedio de entre diecisiete y veinte fotogramas. El proceso tiene otro paso. Una vez que revelaba la película y aprobaba los resultados, hacía copias en blanco y negro, y luego sometía esas copias a otro proceso químico, el viraje a azul, en el cual se sumerge la copia seca en una solución química que reemplaza la emulsión de nitratos de plata ennegrecidos por partículas de color de tonalidad azul.

JPH: ¿Es por eso que vemos de color azul las líneas abstractas, rectas y gestuales trazadas por la luna?

LK: Sí, el proceso vira al azul todos los colores, incluyendo las sombras y las altas luces. Todo lo que es plata es reemplazado por esta reacción química.

JPH: ¿Conocías otros artistas que escribieran con la cámara? ¿Hubo algún antecedente que te resultara interesante, ya sea en la fotografía modernista o incluso en el arte contemporáneo?

LK: En realidad, no. Me considero un lobo solitario. Si descubro que algo ya se ha hecho, no me interesa. Cuando se me ocurre algo, tiene que ver con los aspectos más metafísicos del medio. ¿Qué es la fotografía? ¿Qué es una cámara? ¿Qué es el blanco y negro? ¿Cómo vemos las cosas? Y así. No me interesa entablar un diálogo con otros artistas. Me interesa entablar un diálogo con la tecnología, con la invención. Me interesa la idea de la vanguardia, hacer algo que nadie haya hecho antes.

Lunar Alphabet and Luner Sentence. Exhibition view. Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)..

Lunar Alphabet and Luner Sentence. Vista de exhibición. Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

JPH: Terminaste Lunar Writing I y Lunar Writing II, de 1974, pocos años antes de tu obra hoy icónica Lunar Alphabets [Alfabetos lunares] (1978- 1980). ¿Qué otras obras produjiste escribiendo con la cámara? ¿De qué manera constituyen, para vos, un antecedente para Lunar Alphabets?

LK: Sí, bueno, pasaron varios años entre estos experimentos y el primer Lunar Alphabet de 1978. Para esa obra, junté veintisiete transiciones de la luna tomadas durante muchas noches hasta que la forma de la luna creciente fuera perfecta para representar un carácter particular del alfabeto. Fue preciso rehacer algunas imágenes de la luna, lo que quiere decir que debía esperar otro mes lunar antes de que pudiera captar el ángulo específico que necesitaba. Es decir, aunque estas obras, Lunar Writing I y Lunar Writings II, fueron hechas en 1974, había películas y fotografías que tomé en mi terraza de Nueva York y en otros lugares.

JPH: ¿De qué manera se articula Night Flights: A Diary [Vuelos nocturnos: un diario] en el contexto mayor de Lunar Writing?

LK: La serie Night Flights: A Diary pertenece a un grupo de fotografías que hice abriendo el obturador para fotografiar algo muy oscuro que sin embargo tenía algún tipo de luz alta. La idea se me ocurrió una vez que volaba entre Nueva York, Florida y Texas de noche. Sostenía la cámara con el obturador abierto contra la ventana del avión durante unos pocos segundos cuando el avión pasaba por encima de pueblos o ciudades durante el despegue o el aterrizaje. La sensibilidad de la película y los ajustes de exposición registraban un panorama en movimiento de las luces del paisaje que resultaba bastante encantador. Night Flights: A Diary juega con la idea de un diario, de registrar algo que está teniendo lugar allí.

JPH: ¿Cómo lograste obtener esos maravillosos colores en las distintas series que hiciste a lo largo del tiempo?

LK: Creo que los colores son el resultado de trabajar con distintas fuentes de luz. Como sabes, las ciudades tienen distintas fuentes de luz: mercurio, sodio y tungsteno. Todas ellas producen colores distintos.

JPH: ¿Y recién al entrar el cuarto oscuro podías ver estas variaciones de color?

LK: Sí, luego del revelado color. En otras palabras, es una fotografía sorpresa.

JPH: Y creo que Night Flights: A Diary debe haber resultado toda una sorpresa para ti cuando comenzaste con ese proyecto. Cuéntame cómo exponías el rollo fotográfico.

LK: Hacía un diario por noche en un vuelo. Si volvía a volar, entonces tomaba otro rollo. Las fotografías no eran una mezcla de distintos vuelos sino una secuencia de tomas que hacía cuando el avión se movía, a medida que iba cambiando el paisaje.

JPH: ¿Es decir que las obras que acabamos de ver juntos fueron hechas en un vuelo determinado?

LK: Sí, en una única noche, en un único rollo.

JPH: También has hecho The Vowels [Las vocales], otra inventiva y lúdica serie de fotografías, usando un fósforo como única fuente de luz para escribir en la oscuridad. Pero dejaremos ese tema para la próxima.

This conversation was published in “Leandro Katz,” Arte al Día International 131 (2010): 99-101. Lunar Writings @ Leandro Katz

Artist website: http://www.leandrokatz.com/