Dapper Museum (Paris) Lecture for Lam Metis Exhibition, September 26th, 2001

All images are reproduced for non-commercial scholarly and educational purposes only, in accordance with fair use. Copyright remains with the respective artists, estates, and rights holders.

Illustration #1: Wifredo Lam, 1914, Sagua la Grande

Wifredo Lam had a long and prolific career as a painter, printmaker, sculptor, and ceramist. He contributed to modernism in very special ways. As an insider, he embraced Afro-Cuban subjects at a time when few artists in the western world were exploring similar paths. Lam, master of line, form, and color, learned the lessons of cubism and expanded the parameters of surrealism. He evolved a modernist language which negotiated figuration and abstraction. His works acknowledge such human emotions as pain, suffering, and loss; he referenced war, independence movements, and spirituality. Lam’s art communicates transcultural traditions rooted in the African diaspora not only in Cuba and the Caribbean, but in many countries in the world.

In this talk, I will briefly offer a sense of the artist’s formation in Cuba, Spain, and France between 1918 and 1941. Then I will look at his work from the Havana years from mid-1941 to 1952. During those years, the artist stood at the crossroads of some of the most inventive directions that redefined art in the 1940s in the Western Hemisphere. Lam’s expression of an Afro-Cuban world view was a model [paradigmatic] for future generations of artists who wished to express their transcultural histories in a visual language.

Wifredo Lam’s Mother in 1944

Wilfredo Lam was born in 1902—his father was Wifredo Oscar de la Concepción Lam and his mother was Ana Serafina Castill-–in the sugar farming area of Sagua La Grande, Cuba, twenty-two years after the abolition of slavery. Lam’s mother was of mixed African and Spanish heritage and his father was Chinese [Canton b. c. 1820; from Mexico to Cuba in the 1860s]. The Lam family lived in the Chinese neighborhood in the rural town of Sagua.

Photo of Mantonica Wilson

Lam was raised in both the Catholic and Yoruba religions. The Yoruba people, known as Lucumí in Cuba, came from Nigeria. Today we more commonly use the word Santería to identify the Lucumí religion as practiced. Lam was spiritually guided by his godmother Mantonica Wilson, who was a Changó priestess. She gave him an amulet, a good luck charm, which he kept as a tangible memory of her all of his life.

The young Lam moved to Havana in 1916. He studied at the [Escuela Profesional de Pintura y Escultura,] San Alejandro Academy from 1918 to 1923, under two well-known academic Cuban artists}, Armando Menocal and Leopoldo Romañach]. Lam’s Self-Portrait illustrates the academic style he was developing at the time. The young art student received a scholarship to study in Europe. He arrived in Spain in 1924 and stayed there until 1938. During his fourteen years of residence in Spain, Lam lived, studied, and visited many cities, including Madrid (24-25; 29-31; 33-36), Cuenca (25-29), Leon (‘31-’32), Malaga, Caldes de Montbui, (sanatorium ‘36-37), Valencia (visited ‘36), and Barcelona (July ‘37-May ’38). During his Spanish period, the young artist searched for his voice. He worked with many styles influenced by the academic work of Europeans masters as well as the avant-garde directions of Dali, Picasso, Gris, André Masson, and Henri Matisse. Lam met many European and Latin American intellectuals [Federico Garcia Larca, Alejo Carpentier, Carl Einstein, a writer and art historian, Nicolás Guillén, the Afro-Cuban poet who had just published his first Afro-Cuban poems, Motivos, Valle Inclán, Miguel Angel Asturias] who were sympathizers of the Republican government. He was also connected to several political organizations, including the Organización Anti-Fascistas.

Wifredo Lam. La Guerra Civil (The Civil War), 1937

When the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, Lam went to work at a weapons factory to support the Republican cause. After six months of overwork, Lam became sick and was sent to a sanatorium in Caldes de Montbui, near Barcelona. (He probably had amoebic dysentery.) During his recuperation, Lam made a short trip to Valencia, the temporary capital of the Spanish Republic. He was invited by the Director of Fine Arts (Josep Renau) to do a painting on the theme of the war. The painting was to have been included in the Spanish Pavilion, which [the Minister of Culture and Fine Arts] was being completed for the Paris World’s Fair [1937]. La Guerra Civil was Lam’s first painting, among many that addressed that subject. As can be noted, Lam adopted a strong palette and a tentative cubist structure in which the figures are compressed into a single plane. In terms of the subject, we are reminded of Picasso’s Guernica, a work that protested the bombing of that Basque town by the Italian allies of the Spanish Nationalist forces.

Self-Portrait, c. 1938 [not in exh]

Lam left the sanatorium in Caldes de Montbui in July 1937 to live in Barcelona, where he became part of the artistic community. [He joined artists’ tertulias and participated in a painting and sculpture section of the Ateneo Socialista, which provided him with access to the library, a cafeteria, and work sessions with a live model.] Much of Lam’s Barcelona work shows that he was looking closely at the decorative patterns of Matisse. Self-Portrait, in this exhibition, is one such example. [According to Maria-Lluisa Borràs, Lam purchased a book on Matisse that year. Lam depicted the corner of his Madrid attic studio from memory while depicting the tiles and wall made of colored glass from his Barcelona apartment.]

Because of the deteriorating situation Lam had to leave Barcelona on May 1, 1938 for Paris, where he remained until when the Germans invaded in June 1940.

Douleur de l’Espagne, 1938, gouache on paper. Exhibited in 1939 at the Galerie Pierre.

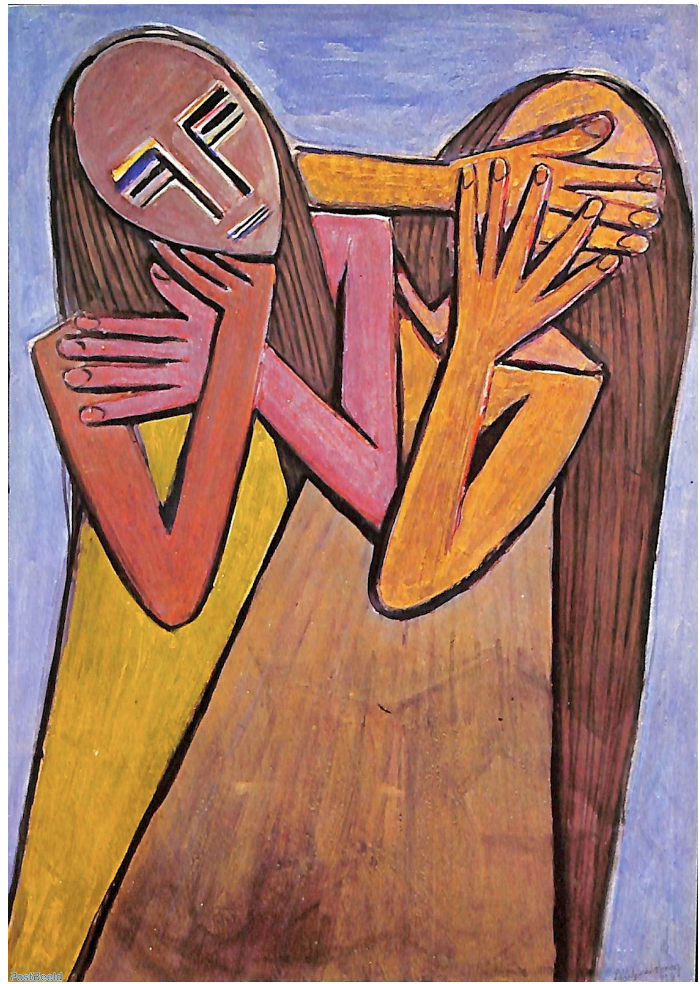

In Douleur de l’Espagne, 1938, the figures of the two women interlock; one grasps her neck, the other covers her face. Their body language expresses the anxiety the general population must have felt in the winter of 1938 when Barcelona was heavily bombed. The gouache, probably painted in Paris after the artist’s arrival, seems hauntingly expressive today, some sixty years later. Most unfortunately, recurring images of war victims still resonate in our political arena.

Wifredo Lam with Pablo Picasso in Mougins, France, 1966 © 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Through a letter of introduction from an artist friend in Barcelona, Lam met Picasso. The Spanish artist introduced him to a group of avant-garde artists in this city and also to the modernist gallery dealer, Pierre Loeb. Loeb gave Lam his first solo show in 1939. I might add that Douleur de l’Espagne was among the works exhibited.

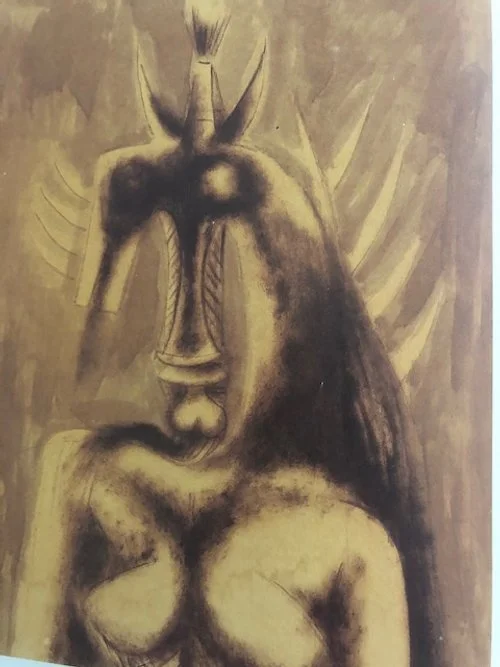

Wifredo Lam. Madame Lumumba, attributed to 1938, gouache on paper

During Lam’s two years in Paris he painted many single figure subjects; he continued to incorporate some of Matisse’s lessons as well as those of Picasso. He also responded to African art, as noted in Madame Lumumba, (not s/d), the work on the cover of the exhibition catalogue. (I might note that the title was added, by Aimé Césaire, after the Patrice Lumumba’s disappearance in 1961). This figure has African sculpture as its starting point. Although Lam had seen African art in Madrid in the museum, he began to respond to its forms in a more specific way, in part due to the tremendous interest in it on the part of modernist artists. It was, after all, the European avant-garde who appropriated African art in redefining their own styles. In so doing the European avant-garde legitimized African art, making it easier for young African and African diaspora artists and intellectuals to pursue their own explorations of their mother-father cultures. (Leopold Sengor, writer & president of Senegal.)

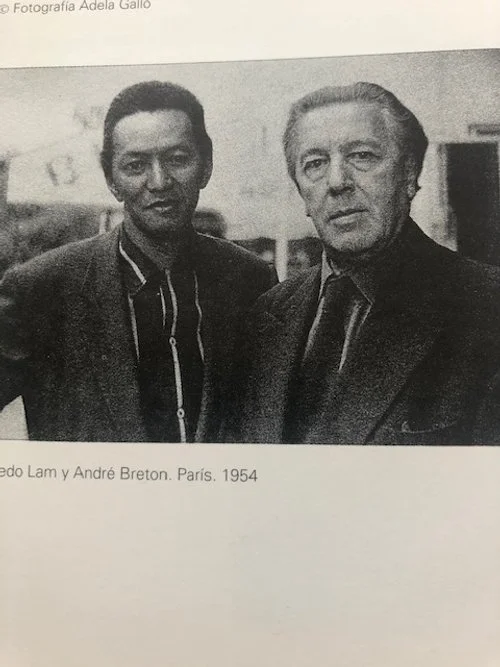

Wifredo Lam and André Breton, years later.

Wifredo Lam with Group Air-Bel

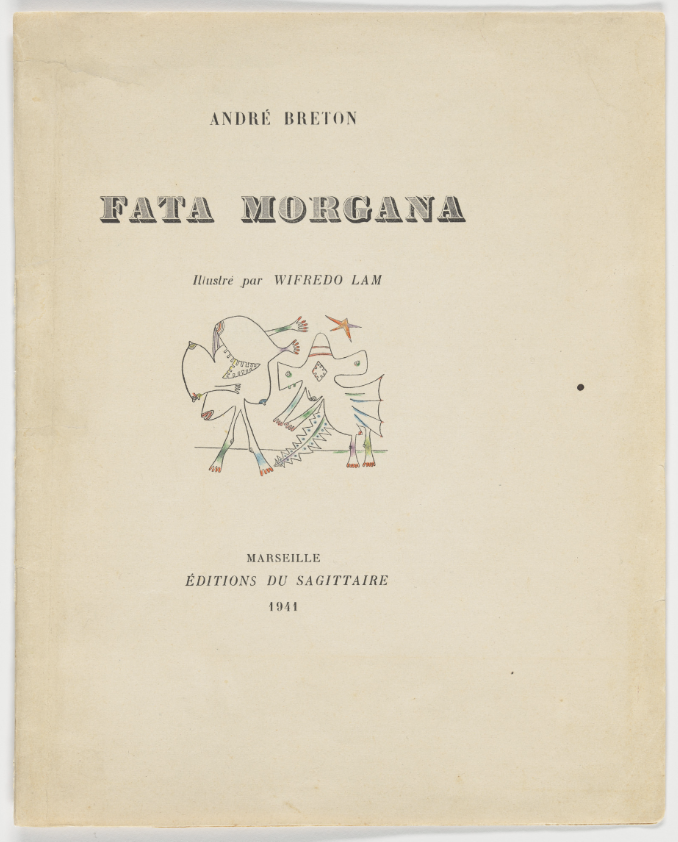

In June 1940 when he Germans invaded Paris, Lam managed to reach Marseilles. Once in the Vichy occupied city, he reunited with Helena Holzer, the German-born biologist with whom he had been living in Paris. The two received money from the Centre Américain de Secours, directed by the American Varian Fry, whose work was supported by the Emergency Rescue Committee in the United States. While awaiting passage out of war-torn Europe, Lam and Holzer and a group of artists and writers, including André Breton, Jacqueline Lamba, Oscar Domínguez, Max Ernst, Jacques Hérold, Victor Brauner, among others, met regularly at Air-Bel, Varian Fry’s home outside of Marseilles. In order to distract themselves from the deteriorating war conditions, André Breton, the father of literary surrealism, organized a variety of parlor games, which included collective drawings intended to emphasize the role of chance and improvisation. Lam, who became part of that group, was invited to illustrate Breton’s poem Fata Morgana.

Wifredo Lam, Fata Morgana, 1941

Here is an example of one of Lam’s many drawings for Fata Morgana. The artist worked within a cubist spatial structure and adopted a Surrealist language of hybrid forms, unconventional configurations, which appeared to spring from the imagination rather than from empirical reality. The line drawing reveals a complex figure combining elements of a woman, child, horse’s head, plant and animal forms, and the moon.

Wifredo Lam and Aimé Césaire, 1968. Congrès culturel, La Havane © DR

On March 25 Lam and Holzer, together with about 350 artists and intellectuals, boarded a freighter bound for Martinique. During a 40-day stopover in Martinique, André Breton introduced Aimé Césaire and his wife Suzanne to Lam. Césaire, a teacher and writer, had also studied in France and had returned to his country due to the war. He and his wife had just published their first issue of Tropiques: Revue Trimestrielle, a magazine about art, politics, and the négritude movement. Lam’s work appeared in that magazine several times in the ‘40s.

From Martinique Lam and Holzer, together with the Bretons and Andre Masson and his family went to Santo Domingo. The Bretons and Masons got visas for New York. Lam and Holzer went to Cuba.

When Lam returned to Cuba, he had been away for more than eighteen years. He was faced with very different cultural, political, and social conditions than those he had become accustomed to in Europe. Cuba was conservative, provincial, and the modern art scene was very small. Nevertheless, Lam formed close friendships with a group of Cuban intellectuals, such as Lydia Cabrera and Alejo Carpentier, and maintained close ties with an extensive network of Surrealist artists and writers in exile throughout the New World during the war years. He participated in national and international exhibitions to the extent that by the time he left Havana in 1952 to live in Paris, he had an international reputation. Lam’s Havana years were among his most productive. In his Cuban capital, the artist hit a new stride.

In 1942 alone, Lam produced more than a hundred works. André Breton introduced Lam’s work to an extended circle of surrealist artists in exile in New York as well as in other countries in the Americas. As a result of Breton’s largesse, Lam’s work appeared in two exhibitions in New York in 1942. La Chanteuse des poissons was included in “First Papers of Surrealism,” the first Surrealist exhibition organized by the French Relief Societies in New York on behalf of the war effort. Lam also had his first solo show at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, where the Cuban artist exhibited regularly through the early 1950s.

Wifredo Lam. Déesse avec feuillage (Goddess with Foliage), 1942.© 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Let’s look at some of the work from the Havana years so we can understand the ways in which Lam foregrounded the Afro-Cuban worldview in his art. Lam employed a variety of surrealist morphologies. He combined plant, animal, and human elements to reconfigure his hybrid forms whose anatomical parts were rearranged and whose sexual organs were interchanged. Lam understood the relationship between aesthetics and creative freedom according to Surrealist theory. Therefore, the artist was able to subvert traditional subjects such as a portrait, a still life, a landscape, and so forth, by redefining the empirical world in terms of the spiritual world. While the Surrealists believed that the spiritual world was part of the unconscious, the Afro-Cubans understood the spiritual world was part of their everyday reality. Lam expressed this world in his art.

Déesse avec feuillage, 1942, combines both human and animal traits. The female gender is identified by the breasts, the male by the phallus and testicles, and the animal species by the pointed ears and tail. The hybrid is configured in a Cubist space in which the anatomical parts are depicted from multiple viewpoints. By overlapping the delicately drawn lines and washes of paint, one figure merges with the other. The multiple-headed deity is one of several mask faces that Lam employs, among other devices, to join the male and female genders and the human and animal species. Such features as the muzzle, mane, ears, and tail transform the otherwise human figure into a hybrid with the features of a horse to create an image known as the femme-cheval (horsewoman). Lam has appropriated Picasso’s bovine and horse imagery to suggest a spiritual state, one in which the devotee and his or her orisha / deity are united. In Afro-Cuban religious ceremonies, an exchange of life force (ashé) occurs between the devotee and his or her deity/orisha. During sacred celebrations, the drums are played in honor of a specific orisha/saint who takes possession of the devotee, referred to as the horse (caballo). In Cuba spiritual possession is often described as one in which the orisha/saint comes down and mounts his horse ("bajarle el santo") or climbs into the head ("suben en la cabeza") where he/she lodges. Lam employed the image of the horse, which reconfigures the human figure, to symbolize the spiritual materialization of the orisha / deity.

Wifredo Lam, The Jungle, 1943

Lam explored the theme of the figure in landscape in order to express sacred and profane beliefs from an Afro-Cuban worldview. In The Jungle from 1943, for example, Lam affirms the interconnectedness between the orisha / deity and nature. The four hybrid figures merge with the surrounding vegetation. The hybrids’ legs conflate with the sugarcane stalks, and their breasts with the papaya fruit from the paw-paw tree. One of the figures holds its arm toward its ear as if listening to the mysteries of nature. Santeria devotees believe in the sacredness of mother earth, commonly referred to, at the time, as the monte. The monte is both a physical place and a spiritual realm where prayer and offerings are made. (In Africa it is the bush.) Deities were born in the monte, and some continue to inhabit its natural elements; others bestow their blessing in the form of ashé, divine force or power. Priests and devotees alike propitiate plants and herbs before cutting them for medicinal or ritual use. The act of cutting plants or herbs is symbolized by the fourth figure with the scissors on the right. The two figures holding plants in their outstretched hands are, in all probability, offering them to the orishas / deities. The group, amalgams of human, plant, and animal forms, dances slowly and rhythmically, as in a bembé, to honor and celebrate those spiritual, life-giving forces found in all aspects of nature.

Wifredo Lam, Malembo, 1943.

Most of Lam's work images the anthropomorphic nature of Afro-Cuban deities /orishas. Two deities most often depicted are Ogún and Elegguá, both of whom retained their primacy from the African to the Cuban context. Ogún, the god of iron and war and protector of the monte, is symbolized by the horseshoe motif. Ogún's presence is equally commanding in Malembo, another signature work of 1943. The title came about when Lam's close friend Lydia Cabrera, a leading authority on Afro-Cuban culture, first saw the painting. She was reminded of evil or a magic spell, which in Cuban Congo parlance is malembo.

Wifredo Lam, Anamu, 1943

Anamu from the same year is a work in which the title also connotes ritualistic practices in Santería. In Afro-Cuban folk practice, many people put two leaves of anamu in the soles of their shoes to ward off evil. Perhaps it was no coincidence that Malembo and Anamu were shown next to each other at the Pierre Matisse gallery in New York in 1944.

Wifredo Lam, Fruta Bomba, 1944. Image from the collection of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. © Wifredo Lam / VEGAP. Reproduced here under terms of fair scholarly use. This painting was in the Sotheby’s Latin American Sale in September 1995.

Fruta Bomba of 1944 is a beautiful painting distinguished by its style, subject, iconography, and provenance. The picture features images of papaya fruit on slender trunks against a background of abstracted palm fronds. The outlines of the forms are delicately rendered, with small touches of paint and fine lines on a white ground, creating the sensation of flickering tropical light. Impressed by the tropical light, Lam sought to reveal its sensory qualities in many works.

Fruta bomba is a term commonly used for papaya fruit. In many parts of Cuba, the word papaya is often avoided because of its sexual connotations of the female genitalia. Lam’s fruta bomba are charged with different erotic associations, namely, the female breasts -- symbols of nurturing. Through the metamorphoses of diverse elements, the papaya fruit doubles for breasts, eliciting the notion of nature as female. If we follow very closely the lines of the thin trunk in the lower right hand of the picture to the point where it is transformed into the vein of a palm frond, we glimpse Lam’s deft punning. The vein of the palm frond seems to support the back of an abstracted image of a seated woman whose anatomy is redefined by the flowering papaya in place of her head, the fruta bomba, her breasts, the tree trunk, and the rest of her body. Along the back of this barely visible, unsuspected hybrid of human form and vegetation are light strokes suggestive of the horse’s mane, an image, which symbolizes that of the femme-cheval. In this painting, as in most from this period, Lam merges Surrealist and Afro-Cuban world views. One calls for the free assertion of the creative spirit, and the other affirms that the animal, vegetal, and mineral kingdoms are spiritually united in nature.

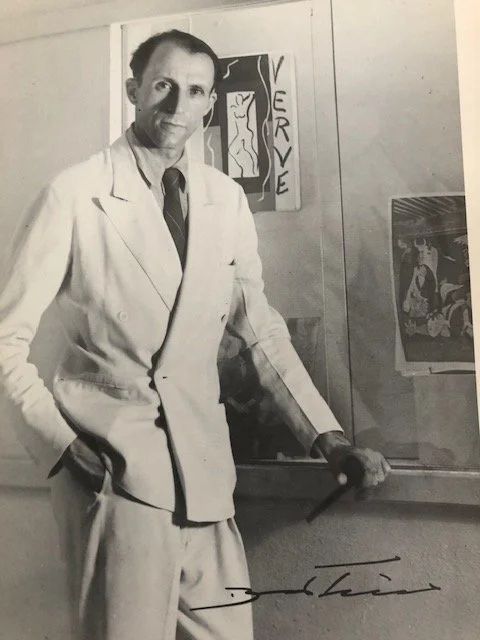

Photo of Pierre Loeb, Havana 1942

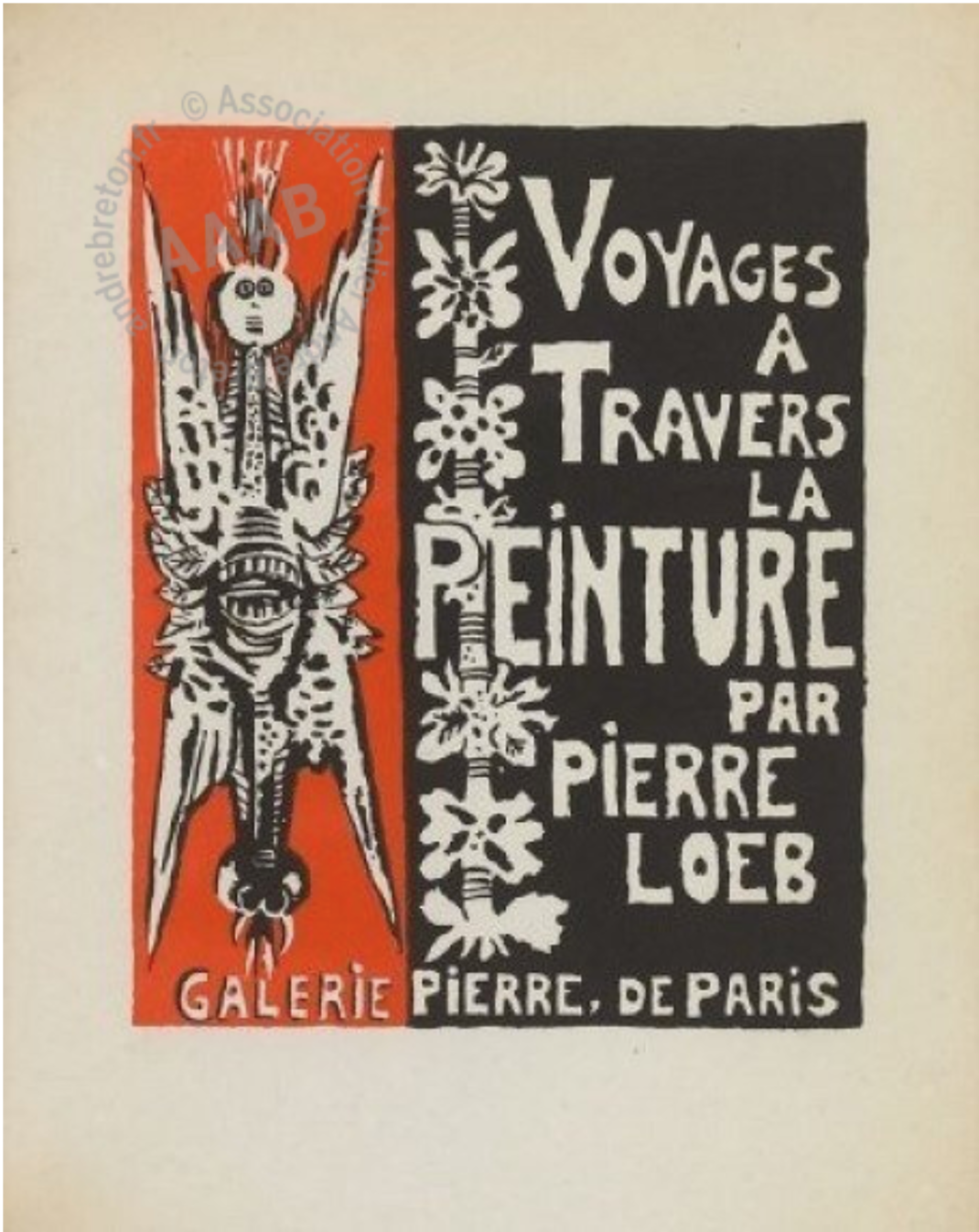

Pierre Loeb in Paris, cover of his book L’Avenure de Pierre Loeb La GALERIE Pierre-Paris 1924-1964

Pierre Loeb, the Parisian gallery owner, lived in Havana with his family during the war years. Here is a photo of Pierre Loeb, Helena Holzer, Wifredo Lam, and Raphael Moreno. Loeb printed an illustration of Fruta Bomba in his book Voyages à travers la peinture in 1945. He wrote: “If there was ever an artist who, by means of fragile lines and immaterial touches, could synthesize the blinding light of his country, its ethnic secrets, the richness of its vegetation, it is he [Lam].”

Wifredo Lam’s illustration for Voyages à travers la peinture par Pierre Loeb, 1945. This is an image of the cover which Lam illustrated for Loeb’s memoires.

There are more images of Elegguá than of any other orisha in the artist’s work. In traditions that derive from Yoruba, Elegguá is the guardian of one’s path; he predicts, prevents, and allows for the vicissitudes of life. The image of the orisha / deity is signified by a little round head in Lam’s work. In actual life, Elegguá’s role as protector is represented by a small votive image commonly placed in a receptacle by the entrance of Cuban homes. These images are made of clay, cement, or stone, with eyes and mouths that are either painted or composed of cowry shells. Although as an adult, Lam did not practice any formal religion--including Santería or Catholicism--the artist did observe the custom of placing an image of Elleguá near the door of his home in Havana.

Wifredo Lam, Altar for Elegguá, 1944

In 1944, Lam rethought the possibilities of the still-life genre when he painted Altar for Elegguá. As noted the painting executed in a pointillist style depicts a table outdoors with an array of barely discernable elements on it. All the images converge in a way that confounds too literal a description of each element. The small votive image of the omnipresent Elegguá, however, is clearly readable. The subject of the altar presented as a still life shows once again Lam’s inclination to utilize a traditional genre in untraditional ways. Common in Cuba during Lam’s time, home altars were made indoors or outdoors (in one’s yard) to honor one’s orisha/saint. Their transcendental importance is attested to by their continued presence throughout the United States and in Latin American communities whose members are influenced by both African and Catholic beliefs and traditions. Domestic altars connect and mediate between the terrestrial and celestial, the material and the spiritual, the personal and the communal aspects of everyday life. Lam chose the format of a time-honored genre into which he inserted subjects from counter-histories to extend the Modernist dialogue.

Wifredo Lam. Rites secrèts, 1950

Here is Rites secrèts another extraordinary painting of 1950 that attests to Lam’s continued interest in the subject of the altar-as-still-life.

Wifredo Lam. The Warrior (Personnage avec lézard), 1947. Le Guerrier and Personage were exhibited in New York at the Gallery Pierre Matisse in spring 1948.

At noted in this close-up of Le Guerrier, Lam depicted the bird-head motif, in these paintings (1947), in a generalized manner, probably to symbolize vultures, which are the divine messengers of Olofi, the supreme deity who is present in every orisha. A Santería devotée believes that Olofi, who is alternately called Oludumare, lives in every human's head. The Yoruba word eleda expresses the concept that an orisha /deity lives in a devotée’s head.

Wifredo Lam. Canaima I, 1947

Lam continued to redefine the human as he had with Le Guerrier. In the series titled Canaima, Lam painted these feral females in flat shapes, displaying open torsos, spikes along their backs, and manes of hair. This body of work is informed by Oceanic art, particularly that of the Sepik River region in Papua New Guinea. Lam had begun to collect work from this area in addition to African art after he returned from a visit to Paris in 1946. Oceanic art was prized by the Surrealists as well as the Abstract Expressionists in the 1940s.

Wifredo Lam. Triangle, 1947

Triangle, from the late 1940s, amalgamates key forms in the Cuban landscape that Lam animated in accordance with an Afro-Cuban worldview. The spiky forms of the plantain trees that grew in the artist’s garden, the animated spirits often depicted by round heads, and the triangular motifs, signifying Abakuá retentions in religious practices in Cuba, are painted in deep, lush tones as if viewed at dawn.

The Abakuá were a religious confraternity founded in the first half of the nineteenth century by people of southern Nigerian origins. There was great interest in the Abakuá in Cuba in the 1940s as evidenced by depictions of that group in contemporary art and in many writings. Lam went to Abakuá, or nanigo, ceremonies with Lydia Cabrera, Alejo Carpentier, the famous Cuban writer, and Pierre Loeb. Lam incorporated diverse Abakuá-like symbols in much of his work, but the symbol of the diamond divided by an arrow into four sections, each section containing a small circle, is noted especially in The Triangle. Lam’s references were part of a broader-based interest on the part of many artists and writers in the Americas. For example, Breton, Max Ernst, and Dorothea Tanning were immersed in diverse American Indian cultures, as were Wolfgang Paalen, Kurt Seligmann, and Barnett Newman. Lam, however, focused on expressing the surviving traditions of the Afro-Cubans or Afro-Caribbeans in his art.

Wifredo Lam. Umbral, 1950

In ending, let’s consider Umbral, a beautiful painting from 1950 in which the central composition features three large diamond-shaped motifs, reminiscent of shields. Lam’s work around 1950 is characterized by a formal vocabulary that reveals a sense of rhythmic movement--a push and pull, a backward and forward thrust. These images are still familiar, they include the diamond forms, horns, lances or pikes, wings, bamboo, and the little heads. Lam’s animated world lies somewhere between the empirical and metaphysical realms.

Lam often drew forms directly on the canvas, creating an interchange between drawing and painting, and surface and line. The dark background creates a sense of depth from which the images spring to life.

In the history of modernism, Wifredo Lam is recognized as a preeminent artist. He both participated in and changed the multifaceted artistic discourses of his time. He achieved these objectives by looking inward and outward and by affirming his complex ethno-cultural identities within an ever-changing Surrealist morphology. Wifredo Lam’s legacy, as I see it, lies in his masterful ability to reinvent surrealist idioms that mediate figuration and abstraction. At the same time, he foregrounded the traditions and beliefs of the Afro-Cuban world view. Surrealism was redefined as was the Negritude Movement.