Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity

By Julia P. Herzberg

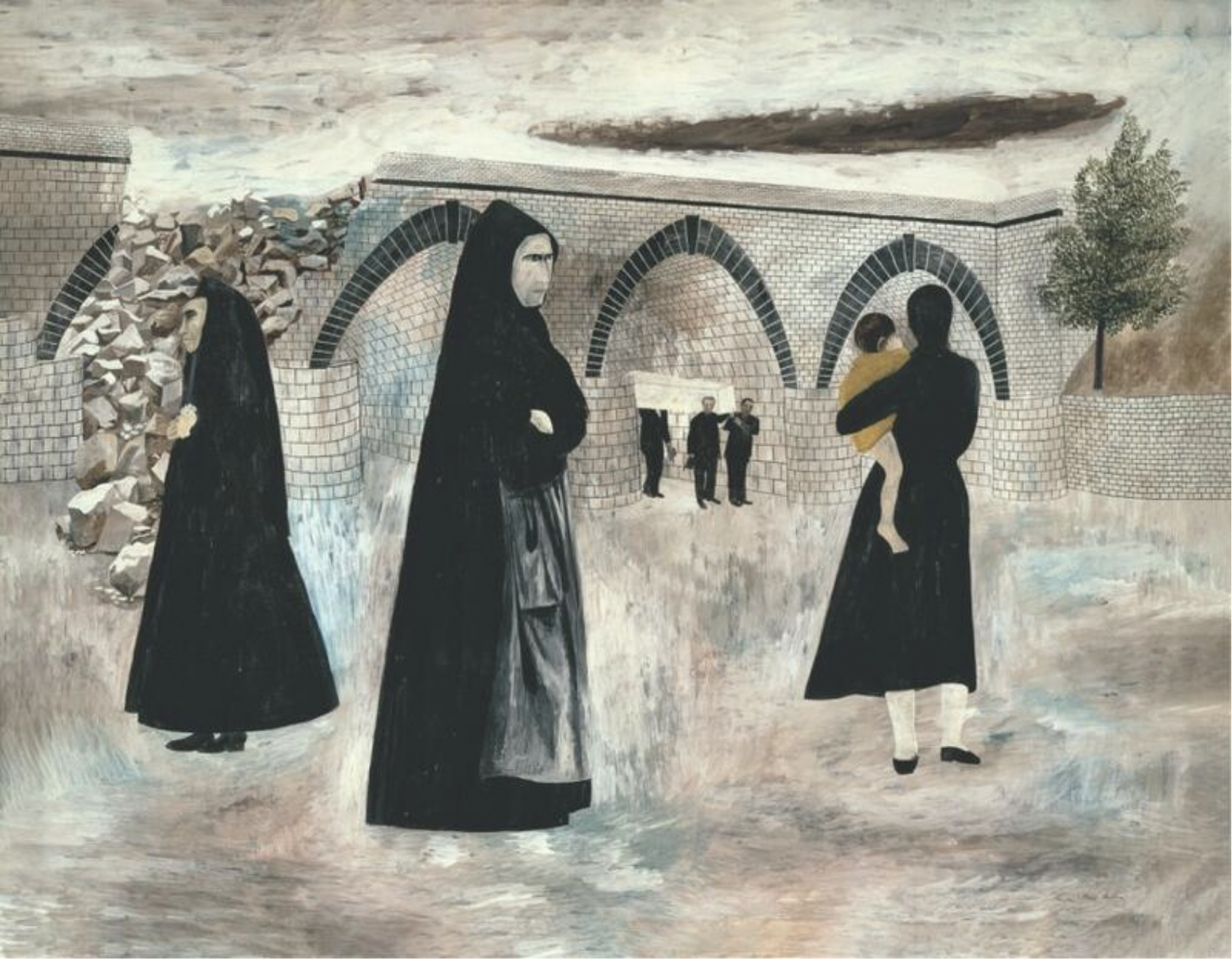

Ben Shahn, "Integration, Supreme Court", 1963, tempera on paper mounted on Masonite, 35 ½ x 47 ½ in. (90.2 x 120.7 cm.) Des Moines Art Center Permanent Collections; Purchased with funds from the Edmundson Art Foundation, Inc., 1964.6. © 2025 Estate of Ben Shahn / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity is the artist’s first retrospective in the United States in almost fifty years. Impeccably curated and designed, the exhibition aims to bring renewed critical attention to one of America’s most consequential modernists. Shahn was a polymath who drew, painted, printed, made murals, and photographed in expressively diverse figurative styles for more than five decades. His richly textured work confronts some of the most far-reaching social and political problems of the last century. The exhibition is divided into seven thematic sections. Each presents a rich array of printed material, thereby informing the viewer of the historical issues relevant to each section: Art and Activism, A New Deal for Art, The Labor Movement, War and Its Aftermath, Age of Anxiety: The Cold War, The Struggle for Civil Rights, and Spirituality and Identity.

Throughout his practice, Shahn (1898-1969) denounced judicial injustices; portrayed the autonomy of ordinary people; championed the rights and struggles of the working class; advocated for human rights; rebuked fascism and McCarthyism; criticized the proliferation of atomic weapons; exposed structural racism and honored civil rights protagonists; embraced spirituality.

Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity

Born in Czarist Russia’s Lithuania in 1898, Shahn’s impoverished Jewish family fled the pogroms in 1906. His family lived in Brooklyn where as an immigrant, he was deeply affected by the harrowing economic, social, and political issues of his time—many of which became the bedrock of his work across many media.

The exhibition opens with the iconic painting The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti. Shahn’s portrayal features three men standing (The Lowell Committee) behind the open caskets of the two Italian immigrant anarchists, who in 1921 had been convicted of the robbery and murder of two workers in a Massachusetts shoe factory. Despite dubious testimony, they were executed six years later. Their trial drew world attention. Shahn viewed the Sacco and Vanzetti case as a miscarriage of justice. In a series of twenty-three works from 1931-32, many exhibited here, the artist portrays a moving story of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, their families, witnesses, jailors, and the presiding Judge Webster Thayer.

Ben Shahn, "The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti", 1931–32, tempera on canvas mounted on composition board, 84 x 48 in. (213.4 x 121.9 cm.) Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Gift of Edith and Milton Lowenthal in memory of Juliana Force, 49.22. © 2025 Estate of Ben Shahn / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

The individual portraits are based on photographic images from magazines, newspapers, and other archival printed matter that Shahn adopted on paper and board, and canvas. Using gouache, pen, and ink, the figures’ stories evoke feelings of solemnity, vulnerability, and tenderness—emotional charges different than those in, for example, Grant Wood’s American Gothic.

Following the Sacco and Vanzetti series, Shahn focused on the trial of Tom Mooney, an Irish American political activist and labor leader wrongly charged with setting off a bomb in a World War I Preparedness Parade in 1916. The falsely accused man was released in 1939. The portrayals of the handcuffed Mooney, his mother, the two untruthful women in Two Witnesses (1932), and the protagonist walking with his wife impart a similar emotional affect to that perceived in the Sacco and Vanzetti series. The subdued mood in the two stories changes radically in Shahn’s painting Father Coughlin (1939), whose anti-Jewish rant on Sunday radio in the 1930s reached weekly audiences of millions. While the subject of Art and Activism is a loadstar coursing through the exhibition, the supporting material in the exhibition case in the same gallery, further illuminates the history of those years. Among the magazines, newspaper photo-clippings, and books is Diego Rivera’s Foreword in the brochure for “The Mooney Case at the Downtown Gallery 1933.” Rivera, assisted by Shahn, was working on the “Man at the Crossroads” (the Rockefeller Center murals).

Following the exhibition’s curatorial path, we enter the next gallery where A New Deal for Art features a stunning collection of Shahn’s photography from 1932 through 1937, traumatic years of the Great Depression as well as the rising face of fascism. The artist’s early silver gelatin prints feature street scenes in Greenwich Village and the Lower East Side with views of ordinary people; shop keepers and their goods; a Black man smoking; young children rollicking; and political demonstrations for varied causes. Shahn drew on his own immigrant experiences when selecting subjects. By 1935 he began working for the government’s Resettlement Administration (later the Farm Security Administration), a New Deal agency, which sent him to the Midwest and the South. There in the dust bowl regions, he captured families living in economic hardship. His dispossessed subjects were farmers, sharecroppers, cotton pickers, among others. Child of Fortuna Family (1935) features a malnourished teenage girl standing under a picture of the Madonna and Child. Shahn’s rendering was published in Archibald MacLeish’s Land of the Free (1938), a photograph that also expresses the humanness of Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936) and Gordon Parks’ American Gothic (1942).

Ben Shahn, "Child of Fortuna Family", Hammond, Louisiana, October 1935, RA6174-M3, gelatin silver print, 8 1/16 x 10 in. (20.5 x 25.4 cm). Elizabeth McCausland papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Shahn created murals for the Resettlement Administration and the Section of Fine Arts. The studies capture the artist’s ability to render complex scenes of people, places, and events in minute detail. Study for Jersey Homesteads mural (c. 1936) presents a montage of immigrants arriving from Europe at the turn of the twentieth century. Their NorthStar was the Statue of Liberty. In the context of immigration, we recall Lasar Segall (1891-1957), a Lithuanian-Brazilian artist whose powerful allegory of emigration and human suffering resounds in Ship of Emigrants (1939-1940).

Following the Study for Jersey Homesteads mural (c. 1936), we become engaged with Shahn’s deep interests in The Labor Movement. Committed to workers’ rights and their need to become unionized, the artist’s subjects include portraits of unemployed men, striking miners, anti-prohibition scenes, steel workers, tradespeople, and families needing resettlement. In the 1940s Shahn became the chief artist and director of the Graphic Arts Division of the Congress of Industrial Organizations-Political Action Committee (CIO-PAC) founded in 1943. His posters and lithographs had texts supporting the government’s goal of ending poverty. For Full Employment After the War, Register, Vote [Welders] (1944) is a powerful image printed for the CIO. The artist’s poster was based on a photograph taken of welders employed in building new Navy ships in 1941. Shahn replaced one of two white welders featured in an original photograph with a Black welder sourced from another photograph. The new image proposed an interracial work force.

During the Great Depression, the world became further menaced by authoritarian regimes in Europe. In War and Its Aftermath, Shahn reacted to the conflicts and horrors of World War II in a multiplicity of scenes often repurposed from the mass media. The text in the offset lithograph This Is Nazi Brutality (1942) informs the American public of Nazi horrors in Lidice, Czechoslovakia where the entire village was destroyed and many of its residents murdered. Italian Landscape (1943-44), classically composed, captures the effects of war on three women, who separated from one another, stand in the middle of a ruined landscape. Shahn’s overlay of washes in tempera speaks to the delicacy and transparency of his painted surfaces. The overhanging dark cloud mirrors the white coffin in the center of the composition; on the left, rubble speaks to death: on the right, the standing tree suggests life. Liberation (1945), in opposition to life and death as well as the future, offers hope symbolized by children at play in the devastated landscape of Europe at the end of WW II. The painting was exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 1954.

Ben Shahn, "Italian Landscape", 1943-44, tempera on paper, 27 ½ x 36 in. (69.8 x 91.4 cm). Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Gift of the T. B. Walker Foundation, Gilbert M. Walker Fund, 1944. © 2025 Estate of Ben Shahn / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Nearby Italian Landscape are the works viewed within the contexts of Age of Anxiety: The Cold War. Shahn’s engagement from the late 1940s to 1960 responds to a series of problematic social and political events. Truman’s and Eisenhower’s anti-communist agenda at home and abroad prompted Senator Joseph McCarthy to hold hearings in which many Americans , accused of being communists, lost their careers. Shahn’s response to the repression of civil liberties is expressed in Discord (1953), Artist and Politicians (1953), and Everyman (1954). During McCarthy’s hearings, Shahn drew a series of distinctive black ink caricatures of the Senator and his lawyer Roy Cohn for the magazine The Nation (May 1954). Parallel to the McCarthy interrogations, U.S. soldiers were fighting in the Korean War. Korea and Goyescas (both c. 1958) are beautiful gesturally expressive images in tempera and watercolor respectively. Goyescas is a stunning response to Goya’s The Disasters of War (1810-1820). In retrospect, Goyescas was a prequel to U.S. involvement in the Suez crisis as well as to the beginning of the Vietnam War.

The artist’s preoccupation with the consequences of the arms race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union are the subjects of Allegory (1948) and Second Allegory (1953), two beautiful temperas that reflect the artist as a force in peace movements. In protesting against nuclear weapons in different media, Fall Out (1958), for example, was an advertisement for a CBS program hosted by Edward R. Murrow. The red, white, and blue screenprint Stop HBomb Tests (1960) made for the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, anthropomorphizes the abstract form of a bomb. As a forewarning of an ultimate disaster, We Did Not Know What Happened to US (c. 1960) depicts a dark blue-black surface with white claws appearing to grasp partial forms of barely visible people.

Ben Shahn, "Second Allegory", 1953, tempera on canvas mounted on Masonite, 53 ⅜ x 31 ⅜ in. (135.6 x 79.7 cm). Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Festival of Arts purchase fund, 1953-7-1. © 2025 Estate of Ben Shahn / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

As noted throughout this text, Ben Shahn was a committed advocate for human rights. In the penultimate section, The Struggle for Civil Rights, the artist draws on several of the most memorable activists who attempted to change the course of human rights. Shahn's ink and ink wash painting of Martin Luther King (1965) was made as a preparatory work for the commission he received for the Time magazine cover published in March 19, 1965. In Shahn and Stefan Martin’s offset lithograph (1968) of the same image, Dr. King’s portrait is accompanied by the prophetic speech in which King proclaims that he has gone to the top of the mountain to see the promised land that he may not get to, but his people will. Here again, text and image unite in a powerful mode that uniquely identifies Shahn’s work. In Human Relations Portfolio (1965), the artist depicted three young freedom fighters, Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, and James Chaney. The three freedom fighters who went to Mississippi in summer 1964 to register Black voters were murdered by the KKK (Ku Klux Klan). The Nine Drawings Portfolio (1965) includes an image of an anonymous Black man with the words written in red: “We Shall Overcome.”